As was the case with many artists of the 1970s, David Bowie was introduced to me via my older sister. Janet brought home Hunky Dory at some point late in the Nixon Administration and when she wasn’t playing it to death, I played it to death. In truth I hardly ever bothered with Side 2 because that’s how my primitive musical mind operated at the time. Side 1 had everything I thought I needed: the radio song, “Changes”; a screamer that Janet and I used to goof on together during car trips (“Oh, You Pretty Things”); and my favorite track, the always haunting and beautiful “Life on Mars”. Once I got to college and lived in close quarters with a more fully developed Bowie enthusiast/savant, Dennis Carboni, I would learn that Side 2 wasn’t just superb (“Song for Bob Dylan”, “Andy Warhol”) but indicative of Bowie’s new genre-busting album and persona to come (“Queen Bitch”).

[I wouldn’t dream of posting anything regarding Bowie without Dennis’ input. His annotative comments appear below, bolded and bracketed.]

It’s been more than a year since Dennis and I spoke of this and many other things the Tuesday following Bowie’s death, in January 2016. He confirmed what I remember us discussing all those years ago, in the wee hours, confined only by the sterile cinderblock walls of our codependent dorm lives — namely, that Bowie wasn’t just consistently 2-3 years ahead of every other rock ‘n’ roll artist in terms of musical direction and fashion sense; he normally hinted at his next departure on the back end (Side 2) of his previous album.

[I like how you wrote, “Dennis and I spoke of this and many other things,” which recalls the lyric, We passed upon the stair, we spoke of was and when — from “The Man Who Sold The World.”]

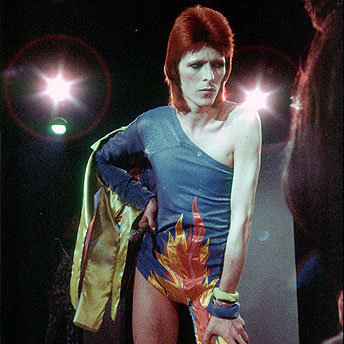

On the generally ethereal Hunky Dory, that clue was, of course, the propulsive and utterly sublime “Queen Bitch”, which heralded the coming of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, one of the great, pure rock (and proto-punk) albums of the decade. To say that Ziggy himself was one of the great “roles” played by any rocker of the period is not necessary, for no one else even attempted this sort of serial shape-shifting back then. Bowie turned this trick 4-5 times throughout the decade (hippie folkster to Ziggy to glam rocker to blue-eyed soul man to Thin White Duke) and competed in this regard only with himself.

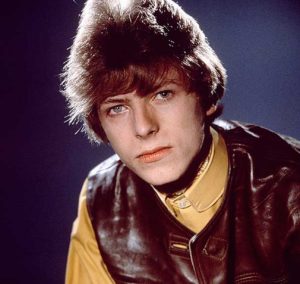

Bowie’s career didn’t begin with Space Oddity in 1969. He’d been around since 1965, when this shot was taken. Pretty mainstream, for the time, and a reminder that these icons we associate with a particular decade didn’t arrive fully formed from the brow of Zeus.

[I’ve been reading the blog, “Pushing Ahead of the Dame.” You may know it, but check it out if you don’t. It’s fascinating. Yes, “Queen Bitch” is perfect because it starts with the acoustic guitar C-G-F progression à la Hunky Dory, then switches right to an electric C-G-F à la Ziggy.]

My sister didn’t own the Ziggy album; indeed, while I knew several cuts well (from FM radio play) I wouldn’t fully absorb it until the early 1980s. She did, however, possess one more Bowie LP: David Live, Bowie’s first official concert release where, once again, he shows us a transition in the making: from the hard-edged glam of Diamond Dogs to the Philly soul of Young Americans. I am not ashamed to admit that I love this particular Bowie period, this dalliance in what he later, somewhat ambivalently referred to as “plastic soul”. It does shame me to admit, however, that until I was 12-13 years old, I thought this dude’s name was David Live. Indeed, he looked and sounded so different from the Hunky Dory-era Bowie, I thought they were two different artists.

•••

Dennis Carboni (better known by our particular cohort as The Bone) arrived at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Conn., with several well developed musical obsessions. We didn’t bond over them all (I was as confounded/repulsed by The Human League as he was by Neil Young) but we did find common ground in ELO and Steely Dan — and it was through him that I learned to love and appreciate Bowie, and Prince. Part of the reason I was so drawn to these artists was indeed The Bone’s singular, boundless and utterly guileless advocacy. It wasn’t enough for Dennis to know every song on every album, to know who played each instrument on each track. This was the level of his relatively casual Steely Dan obsession, for example.

“Thin White Duke” Bowie — the look The Bone was after early in the 1980s. This image was taken from the same session that produced the cover for the ubiquitous ChangesOne album.

He took it up several notches for Bowie, more or less patterning his own persona, physical presentation and style on the Thin White Duke and Berlin Bowies of the late 1970s — the Bowie of Station to Station, Low, Lodger and Scary Monsters. That meant wearing his hair like Bowie did during his famous 1979 Saturday Night Live appearance, wherein he performed “Boys Keep Swinging”, “TVC15”, “The Man Who Sold the World”. It meant selling his stereo to buy a sewing machine, so he might properly peg his jeans — often installing zippers to turn this trick. It meant shaving his legs, an act that mystified fellow jocks on the track and football teams at staid Orville H. Platt High School in Meriden, Conn., even at notoriously boho Wesleyan.

It goes without saying that Dennis owned every last bit of vinyl produced by Bowie through 1982, when we all showed up in Middletown as freshmen, and, for the record, he was free to sell his stereo because his roommate had a better one. Through Dennis I came to know each Bowie album quite intimately. For example, over a period of weeks our freshman year, Dennis chaperoned my close listening of Pin Ups, Bowie’s beguiling album of ‘60s covers, issued in 1973 (we loved it; Rolling Stone hated it). Much has been written these past few weeks about the generosity of Bowie’s artistic spirit and he did collaborate with, write songs for, and serve as commercial and artistic patron to so many: Mott the Hoople, Iggy Pop, Lou Reed… And so it made sense that Bowie, on Pin Ups, would shout out to the Yardbirds, Them, early Pink Floyd and several more influences from his ‘60s youth — when Bowie was not some callow teen but leader of his own folky band.

Yet even so, who takes time between the triumphs of Aladdin Sane and Diamond Dogs to put out an entire album of covers? With Twiggy on the cover alongside him?

The coolest thing about Pin Ups, however (or so I learned from The Bone), was Bowie’s cover of The Who’s “I Can’t Explain”. This was the age of turntables, of course, and Dennis revealed to me that this track could be played as a dirge, at the standard 33 rpm, or as a piece of pristine proto-punk when one simply toggled the turntable to 45 rpm. That blew my mind: Best secret vinyl ruse since the Paul is Dead “campaign”.

[I gave all my Bowie vinyl to my sister. I’m an idiot. I know. Without the vinyl, I wasn’t able to re-hear the amazing 33@45 “I Can’t Explain”, so I just installed the 45rpm app and listened to it on iPhone. Memories came back strong!]

The following winter I had moved off campus, to 114 High St., while Dennis and perennial roommate/stereo sugar daddy Dave Rose made house in a different double somewhere in the miasma of late-60s, brutalist dorm architecture that was (and remains) Butterfield C. It was here one night, sometime during our sophomore year, that I popped over unannounced (that’s what people did back in the pre-mobile age) only to find the lights down and “Heroes”, the single, playing on the stereo. Rose was operating a baby spot, wherein The Bone — effectively bathed but darkly clad in coat and tie — could be seen mimicking Bowie’s expressions and hand-gestures from the Heroes album cover. This went on for some time; such was the power of the kooky, spot-on spectacle. No pictures were taken. Again, such was the age we lived in at the time. Today it would surely have been captured on video and, by now, achieved the rank of Internet Sensation.

The following winter I had moved off campus, to 114 High St., while Dennis and perennial roommate/stereo sugar daddy Dave Rose made house in a different double somewhere in the miasma of late-60s, brutalist dorm architecture that was (and remains) Butterfield C. It was here one night, sometime during our sophomore year, that I popped over unannounced (that’s what people did back in the pre-mobile age) only to find the lights down and “Heroes”, the single, playing on the stereo. Rose was operating a baby spot, wherein The Bone — effectively bathed but darkly clad in coat and tie — could be seen mimicking Bowie’s expressions and hand-gestures from the Heroes album cover. This went on for some time; such was the power of the kooky, spot-on spectacle. No pictures were taken. Again, such was the age we lived in at the time. Today it would surely have been captured on video and, by now, achieved the rank of Internet Sensation.

[I’m glad you have these memories; it feels so good to hear these things that happened… I know it was me, but I just didn’t store the memories well enough. They come back when you trigger them. Funnily, for me it’s easier to remember things like eating pancakes (or Tex-Mex stuff?) and listening to Hall & Oates’ H2O down at your place on High Street.]

•••

Having spent the better part of my freshman year boning up, as it were, on the complete Bowie catalogue, I was in a position to turn up my nose at a few things: The first was Changes One, a compilation, Bowie’s first, released in 1976. At Wesleyan, I’d estimate this album was a mainstay in 75 percent of the record collections I happened upon. As ever, however, the “best of” route proved a dangerous step on the path toward self-administered down-dumbing. Because Changes One merely scratched the surface of Bowie’s enormous appeal. I took to evangelizing my peers to hit the Princeton Record Exchange — a traveling music flea market that showed up on campus twice a year selling perfectly good used vinyl for 10-25 cents a pop — to properly fill out their Bowie collections.

I also turned up my nose at what many consider Bowie’s last decent album. Let’s Dance hit in the spring of 1983 and it featured some good quasi-pop songs, including a few (the title track, “China Girl”, “Modern Love”) that garnered serious radio play — a term recently been expanded to include “video” play on the nascent MTV and terrestrial TV knock-offs like Greater Boston’s V-66.

Bowie toured in support of the album and I had the pleasure of seeing him at Schaefer Stadium along with 60,000 others in the fall of 1983 — my very first stadium show. David live would prove magnificent in a pale-yellow, double-breasted linen suit, holding the audience in his palm by dint of a prowling, feline stage persona, these new hits, and two dozen further samplings from that massive catalogue of his.

But his previous decade of prolific hit-making, risk-taking and trail-blazing would ultimately prove the rub when it came to Let’s Dance, not to mention the dozen or so albums Bowie issued thereafter: They didn’t measure up. In the immediate sense, Let’s Dance followed a run of albums that was nothing short of spectacular: Station to Station, Low, Heroes, Lodger and Scary Monsters are masterpieces all, each utterly unique and 2-3 years ahead of our would-be tastes. Thanks to Bowie’s seamless transition to the video format, Let’s Dance sold well and kept the dream alive, as it were. But artistically, it was nothing terribly special — indeed, it veered dangerously close to pop, something Bowie always hovered above.

In the longer term, for most all of us (including professional tastemakers these last 30 years) Let’s Dance would prove Bowie’s last true hurrah. He continued to issue a diverse collection of albums; I particularly liked the IDEA of his simply being part of a band (Tin Machine, 1988-92) but I can’t say that this notion — and the three albums it produced (two studio, one live) — moved me much.

[I don’t have anything to add here apart from the fact that I love Let’s Dance, even though I know the “rock” critics do not. I do think Bowie has been somewhat relevant of late, in both 2013 and 2016. But that may be, sadly, because first he returned after a decade away (issuing Next Day, a powerful album) and then released the greatest final statement (Blackstar) in the history of rock.]

•••

Many of the retrospectives and obituaries I’ve read since Bowie’s January passing hint at this last point of contention: that while he assiduously avoided repeating himself — and the cynical formulas that would have sold out once-a-decade nostalgia tours, à la The Rolling Stones — Bowie’s cultural relevance tapered off markedly following Let’s Dance.

While this observation is undeniably true, it does gloss over the fact that from 1971 to 1983, Bowie ruled the post-Beatles world. And no one in the rock ‘n’ roll era, not even the Fab Four, was ever so consistently mode-shattering and commercially popular over such a long period of time. We can throw right out the window any and all further comparisons to the Stones, Zep, REM or any other “bands” — for these were collections of talents, while Bowie was just one man, an individual who assembled bands, looks, sounds and trends pretty much on his own. No individual can claim such an artistically varied, unfailingly daring but still popular run of form.

Dylan? Yeah, he went electric and did a country album. But he shifted shape hardly at all in terms of persona. The only individual who has even attempted this sort of long-term trick is Prince, who managed 6-7 years of arguably comparable output (and sexual non-conformity) before eventually bowing under the pressure.

[Do Michael Jackson or Madonna merit mention?]

Only a fleeting one, you Bone. MJ was a child star, then a full-blown pop icon on the strength of two albums (Off the Wall and Thriller) before riding out his days as a physical, commercial and emotional oddity — not an artist or even a reliable popsmith. Madonna had the shape-shifting down but not 1/10th Bowie’s talent or vision. Lady Gaga works in this space but managed just 2-3 years of relevance — now she’s singing the national anthem at Super Bowls.

Bowie turned this very difficult trick for 12 years, all the while fostering the work of others, all the while pushing the popular envelope, not just in music but in film and fashion. Indeed, no one in the history of rock ‘n’ roll was so “mainstream” successful while simultaneously inhabiting the avant-garde.

[Are critics afraid to speak of this? Do they think they are belittling all the other artists if they mention the concept you discuss? It’s a perfect closing.]

We’re not quite done: In the 2-3 weeks following Bowie’s death, there was indeed a sustained outpouring of affection for the man, his music, that enduring commitment to the avant-garde, and a basic humanity that never did get lost amid the trying-on of so many on-stage personae. To me, a pair of paeans stood out.

The first was an 18-minute podcast segment produced by The New Yorker, wherein reporter Sarah Larson sat with a fellow from the techno-jazz ensemble that backed Bowie on his last album, Blackstar, issued just weeks before his death. The story of their meeting up is interesting enough on its own: Apparently Bowie wanted to do a jazz-inspired album and anonymously scouted these guys at a couple NYC clubs. He floated the idea of this project via email. Utterly gobsmacked, they agreed. Bowie then collaborated on the recording without the slightest trace of ego — never mentioning to the band that he was terminally ill, for example. Near the end of the segment, Larson asks the saxophonist, Donny McCaslin, whether he’s listened to Blackstar since Bowie’s passing. Twenty seconds of dead air ensue, as the poor bastard tries to gather himself. No, not yet.

The second was a documentary that aired on PBS called “Five Years”, where the filmmakers detail five of these astounding musical and theatrical transitions Bowie underwent at the peak of his powers. It’s now available on Hulu and Showtime OnDemand. I can’t recommend this doc highly enough, as it encapsulates and confirms much of what I describe above, in far greater detail, deploying Bowie’s own words, those of his various collaborators, and an amazing collection of period images, sound and video — 75 percent of which I had never before seen or heard. Bowie himself makes the point that he really didn’t see himself as a rock ‘n roll star, more an actor who takes on a role, immerses himself therein, then discards it for the next one.

That sentiment seemed to me spot on (we’ve barely touched on the man’s film work, which also fits neatly into this continuum), but grasping it too tightly does risk our diminishing the incredible body of musical work that grew out of this role-playing — a catalogue that never felt derivative of itself, that was often popular but only rarely veered into “pop”. King Crimson’s Robert Fripp, a featured guitarist on Heroes and Scary Monsters, had some really cogent things to say in Five Years about the making of those two albums, and Bowie’s music in general. He greatly appreciated the freedom he was granted to spin his twisting, screeching guitar riffs, adding what he considered elements of “danger” to otherwise straightforward melodies. Listen to a track from Scary Monsters like Fashion or It’s No Game. You’ll understand what Fripp means.

This documentary was the first time I’d ever seen Fripp speak on camera. He comes off like an avuncular but highly mischievous university semiotics professor, one who just happens to be an aging guitar god/visionary. He points out that Bowie had a genius for using scatalogical things like a Fripp guitar lead — or broadly provocative themes like androgyny, race-mixing, fascism and drug use — to purposely unsettle the listener. In the doc, Fripp amplifies the point, explaining that it’s precisely this menace that separates mere pop from “rock ‘n roll”. The Brit allows that idea to hang there for a moment before sitting up a bit straighter in his chair and adjusting his gaze to look more or less straight into the camera. Lifting an eyebrow ever so slightly, Fripp explains what that danger truly means to the listener: “It means you might get fucked.”