Heartiest New Year’s greetings from the band to everyone out there in Mumbles Nation. We wanted to share some content here and encourage you to monitor this space, as 2026 is shaping up as a busy year on the ol’ gig calendar. We should soon have news about a cool April date at a new, prestige venue. Well, new to us… Also, our first Fryeburg Fair is lined up (first week in October), and several more new-venue dates are in the works.

Meantime, however, we ran across this podcast and couldn’t help but share it. “Flightless Bird” ranges all over the map in terms of subject matter but this one, on tribute bands, hit home. Because, as some of you well know, Pocket Full of Mumbles started out as a Simon & Garfunkel tribute duo. Yes, we have evolved way from that enterprise, adding new sounds and personnel, while widening our content to include originals and covers of many different artists. Just this winter we’ve added new ones from Little Feat, REM and The Pixies.

Yet facts are facts: The band was born in the tribute milieu and this podcast discussion really got us thinking about what that meant at the time, and what it means now.

Of course, our name is enduring. Pocket Full of Mumbles refers to a specific lyric from “The Boxer,” and we don’t see that changing or evolving.

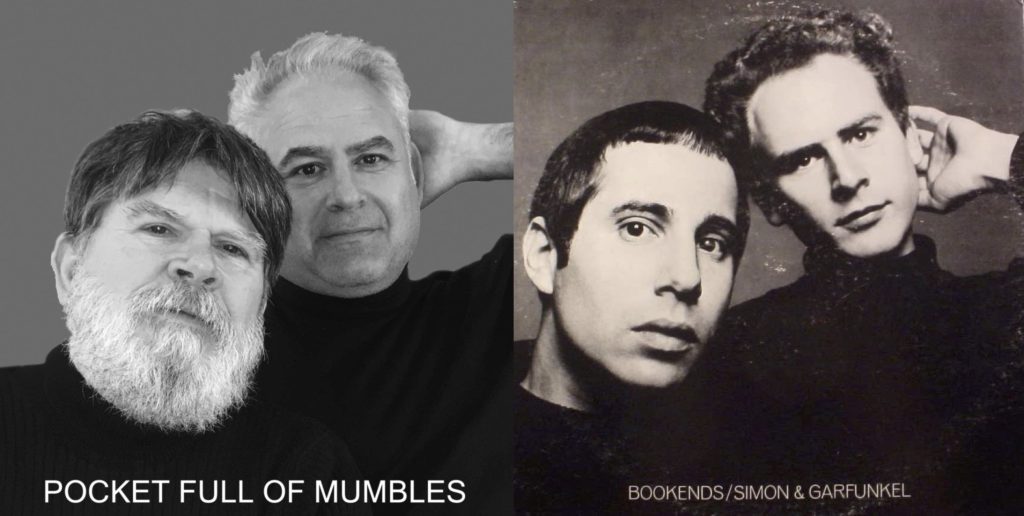

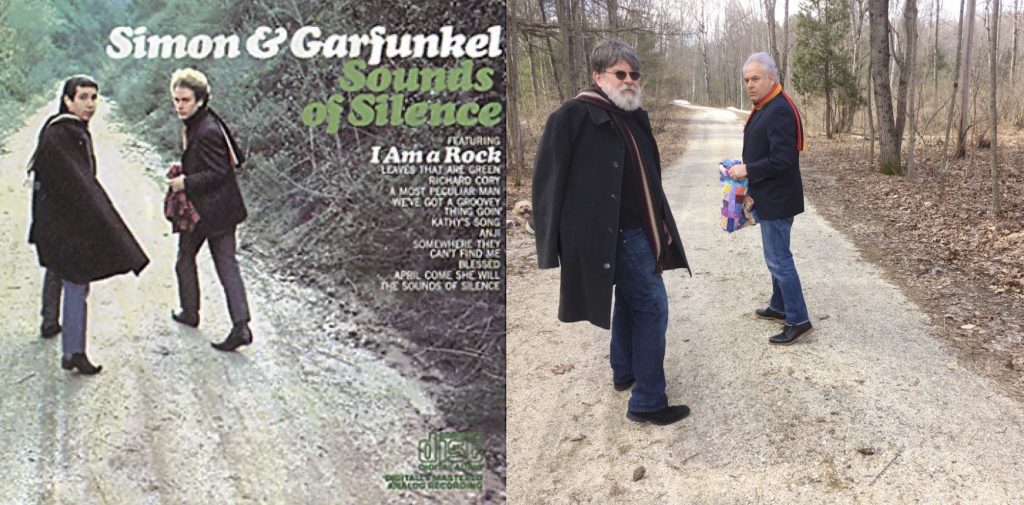

But unlike many of the tribute bands operating today — and there are hundreds working today and making good money from coast to coast — we Mumbles never much indulged in cosplay. Early on we had some fun re-creating famous S&G covers. See here some examples. But we never took that whimsy to the stage., whereas many tribute bands purposely perform, dress and promote themselves on- and off-stage in ways that pay homage to the original bands. As one pod guest put it (he performs in an AC/DC tribute ensemble), it’s often the goal to create a sort of Broadway-show version of the original lineup from night to night.

There was quite a bit of discussion regarding what distinguishes cover bands from tribute bands. This doesn’t seem a very fine line to us. Cover bands do not indulge in much cosplay; how could they? You can’t dress up and act like a dozen different bands during a single performance. I mean, think of how many wigs that might require!

Cover or “bar’ bands also seem to place more emphasis on interpreting recognizable songs in a different but effective way altogether. We often say, “You may know the Simon & Garfunkel version of America but you can’t truly appreciate the song until you’ve heard it with pedal steel.”

The Mumbles have moved well past the tribute thing but we still perform half a dozen S&G songs and we don’t judge. Tribute bands go that route today because they ‘re popular and can be lucrative, which is just another way of saying, “Many folks who patronize live music venues want to hear what they know.”

There can be great creativity in the exercise, not just dressing up but crafting the brand: Apparently, there is a tribute ensemble out there that opens with a set of Foreigner, followed by another in the “role” of Journey. The are, naturally, called Foreign Journey. Some original acts actually mine established, skilled tribute bands to replace aging, deceased, disaffected members. Journey famously plucked a tribute lead singer (based in the Philippines!) back in 2007, when the original Steve Perry stopped believing.

In the end, a good set, ably performed, is its own reward regardless of genre. I saw an outfit called The Outsiders deliver a truly excellent Tom Petty show at Bell’s Brewery in Kalamazoo two years ago. First rate, and they didn’t do any “characters” or costumes. [If you think drunk middle-aged women go crazy when they hear a spot-on version of “Last Chance for Mary Jane,” you should experience that phenomenon in the Midwest.]

By the same token, if you play in a Grateful Dead tribute band — as Mumbles drummer Jeff Glidden has (along with an Allman Brothers outfit called Wake Up Momma) and you don’t get stoned with fans between sets, you’re not really trying.

For us, this pod reminded us of these bands, how all types of bands, are conceived. Mike Conant and Hal Phillips had played together in a couple different bands starting circa 2008. At some practice five years later, Mike started noodling the melody of “Leaves That Are Green,” off Sounds of Silence. I joined him and sang the whole thing, start to finish. We looked at each other and said, without speaking, “Well then. Here’s someone who likes S&G as much as I do.” And the rest is history…

PHILADELPHIA — When we learned my daughter Clara would matriculate at the University of Pennsylvania, naturally her dad was thrilled: Here was my chance to make a proper pilgrimage to The Palestra, the most storied college basketball venue of the 20th Century.

PHILADELPHIA — When we learned my daughter Clara would matriculate at the University of Pennsylvania, naturally her dad was thrilled: Here was my chance to make a proper pilgrimage to The Palestra, the most storied college basketball venue of the 20th Century.