[Ed. This story appeared in March/April 2003 issue Golf Journal magazine.]

The Swift River started rising in the rural Massachusetts town of Greenwich on Aug. 14, 1939, and soon enough the fairways at Dugmar Golf Club had become unseasonably soggy. After a time the layout’s bunkers and teeing grounds were completely submerged, and had the pins not been removed years before, their flags would have been some of the last things visible before this 9-hole track and the rest of Greenwich were lost for good.

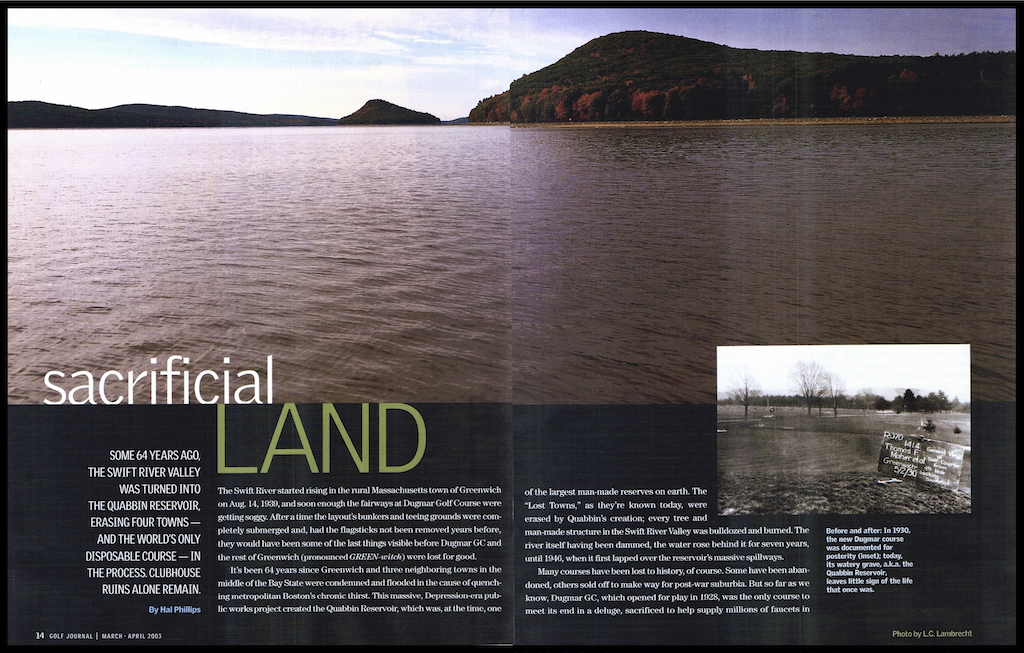

It’s been 68 years since Greenwich and three neighboring bergs were systematically condemned and flooded, all in the name of Metropolitan Boston’s chronic thirst. This massive, Depression-Era public works project on whose ass the loss of Dugmar GC was but a pimple, created the Quabbin Reservoir, then the largest man-made, fresh-water reserve on earth.

The Lost Towns, as they’re known today, were literally erased by the Quabbin’s introduction; every tree, every man-made structure in the Swift River Valley was burned or bulldozed to make way for it. The river itself having been dammed, the water rose behind it for seven long years, until 1946, when it first lapped over the reservoir’s massive spillways.

By then Dugmar GC had been largely forgotten — but not erased, for memories are made of stronger stuff.

Other layouts have been lost to history, of course. Some have simply been abandoned; others were sold off to make way for post-war suburbia. But so far as we know, Dugmar GC — opened for play in 1928, hard by Curtis Hill — was the only golf course to meet its end in a purposeful deluge, sacrificed (along with four 200-year-old communities) to supply tens of millions of faucets in larger communities some 60 miles east.

Hundreds of golf clubs were built, as Dugmar had been, during the heroic age of Jones and Ruth as the moneyed classes sought to bring the same sort of bravado to their own lives (not to mention a place to drink hooch in a country gone dry). More than a few of these establishments “went under” during the ensuing Depression, but none quite like (nor quite so literally as) Dugmar Golf Club, for unlike their unwitting, high-living contemporaries, Dugmar’s developers KNEW the club’s fate before the course was ever built — before the bentgrass was imported from southern Germany, before the elegant stone patio was laid beside the farmhouse-turned-clubhouse, before the first crate of Canadian Club was hidden from view.

It was, in short, a set up: a crafty land deal with golf at its core; a trifle built to amuse its backers, for a time, before enriching them at the public’s expense. “Those guys knew what they were doing; they made out,” recalls a chuckling, 85-year-old Stanley Mega, who caddied at Dugmar GC and still lives close by Quabbin’s shores, in Bondsville. “Those guys knew the reservoir was going in and they made a killing.”

In essence, Dugmar GC was conceived and ultimately proved to be the world’s first and only disposable golf course.

•••

“Those guys”, the men behind Dugmar Golf Club, were a pair of canny executives from the Chapman Valve Co. in Springfield, then and still today the hub of Western Massachusetts. In 1924, Chapman President Thomas F. Mahar and Treasurer John J. Duggan together purchased a pleasant chunk of property some 30 miles northeast of their offices — in the tiny hamlet of Greenwich (pronounced green-witch), conveniently located on the Athol branch of the Boston-Albany Railroad.

The towns of Greenwich, Dana, Enfield and Prescott were poor farming communities and had been for centuries, but their lakes and myriad points of river access were popular with holiday-makers from the big city. It was common for Springfielders to own summer camps and cottages up there.

Duggan and Mahar had far grander plans. After paying $6,850 for 147 acres of abandoned agricultural land, they immediately set to work refurbishing the property’s existing farmhouse. In 1925 its value was assessed at $2,000; two years later this homestead was valued at $7,000. Next Duggan and Mahar built a striking fieldstone lodge on the south-facing slope of Curtis Hill. Completed in 1926, it was assessed a year later at $12,000.

Once an additional 15 acres had been purchased, they commissioned Orrin Smith to design and build Dugmar’s golf course. Opened in 1928, the nine-hole layout occupied ground southeast of Curtis Hill, in full and magnificent view of the lodge with its distinctive stone-pillared porch.

The layout at Dugmar — a moniker created by combining the surnames Duggan and Mahar — was not some bit of amateur course design. Smith had been a respected and quite prolific New England architect, one who had apprenticed with Willie Park Jr. and Donald Ross before starting his own Hartford, Conn.-based practice in 1925. Dugmar GC measured a stout 3,160 yards from the back tees, boasted state-of-the-art putting surfaces of South German bentgrass, and featured 8,000 feet of underground irrigation pipe, something only the better courses could afford in those days.

“It was an unbelievably beautiful place right there in the valley. I’ll never forget it,” says Mega. “It was a very nice golf course, but I was too young to play back then. We caddied. I used to travel up there with Dave Belisle and Jimmy Fitzgerald. We spent a lot of time up there. If I made 35 cents a round, well, that was great!”

Mega and his older brother Alec would often rise in Bondsville, their tiny home town just south and west of the Swift River Valley, and take the train up to Greenwich. Or they’d hitch a ride via Belchertown on Route 21, the only paved road that ran north/south through the watershed. “It was quite a place up there. A few of the holes I forget, but I remember everything else. Between the 1st and 2nd there was a big stand of pine, sort of squared off. There were more woodlands guarding the 3rd, on the right. That’s where I found all my golf balls, you know. Now that was a nice hole, a great dogleg par-5.

“The greens were what always impressed me,” Mega continues, gathering steam. “Tiny things. You had to be accurate! And boy were they in great shape. Beautiful. Imported! People were always bragging about how they were imported. In fact, before they flooded the place, someone came in, picked up those greens and took them away! … I just caddied up there but my brother, he was a good golfer. He played Dugmar quite a bit. So did another good player, Whitey Wisnewski, who was almost like a pro. He used to play with [Henry] Bontempo here in Springfield. He played the best around. Good golfers played up at Dugmar. I still remember.”

The 1928 opening of Dugmar’s 9-hole course fulfilled the “Phase I” vision of its founders. This was now a fully fledged country club, complete with a golf course, a clubhouse featuring several guest rooms and a lively social calendar — because, lest we forget, this was the decade of Prohibition.

“There were raucous parties up there; they certainly took advantage of the remoteness of the place,” explains J.R. Greene, an historian who’s been researching Quabbin and the Lost Towns since 1975. “The Greenwich Village train stop was very close to the golf course, a short walk. So it was very convenient for these ‘bit city outlanders’ to travel there from Springfield. And I have it on very good authority that Dugmar members brought plenty of liquor up there — and women who weren’t necessarily their wives. This was a heavily Yankee, Protestant region; there were no bars or taverns there, even before Prohibition. So that sort of behavior was duly noted.”

“It was a wild place,” Mega concurs. “To be served drinks, well, you had to know the right people. There was a lot of drinking. Those guys were really something; they knew what they were doing.”

The Dugmar clubhouse used to sit on Curtis Hill. Today its shell sits abandoned and secluded — on Curtis Island.

•••

Duggan and Mahar’s Phase II vision for Dugmar GC remains, to this day, the subject of some speculation. The idea of creating Quabbin Reservoir, you see, was put forward as early as 1919; the state Legislature formally proposed the measure three years later. In 1927, the Massachusetts State Legislature legally impounded the mighty Swift River, thereby clearly declaring its intention to take the towns of Dana, Prescott, Enfield and Greenwich by eminent domain — an act that would eventually displace some 2,500 residents.

In other words, by 1929, when Dugmar Golf Club’s curious, boisterous run was just beginning, many residents of The Lost Towns had already sold their condemned properties to the state and moved their lives elsewhere. Others had sold out and rented their own homes, buying time to determine where and how exactly their lives might continue.

“This area was dying unless you raised livestock or fowl. For the younger generation it was an obvious opportunity to get out and start fresh,” says Greene, whose history The Creation of Quabbin Reservoir was reissued by Performance Press in 2001. “But for people in their 40s and up, their lives were torn apart – during the Depression no less! This was a tragedy. And of course, these folks didn’t want some peckerwood from the state telling them to move out. So you have to remember this was a very wrenching thing. There was no job-relocation assistance. Nothing like that. They had to find a new house, a new job, a new life — in the heart of the Depression.”

So why build a remote country club here, on land legally destined to sit under 40 feet of drinking water?

“It was an investment,” Greene says flatly, fighting a wry smile. “Just a part of the game Duggan and Mahar played. I believe they knew the reservoir was going to happen and this golf project was pure speculation on their part. I’ve had older residents say as much to me. It’s received wisdom, if you will.”

Of course, Duggan and Mahar claimed no such wisdom, not publicly anyway. They didn’t claim ignorance of the proposed reservoir project; when pressed in court, they claimed to have considered the Quabbin in the same way many Commonwealth residents still view certain state-funded, public works initiatives: I’ll believe it when I see it.

In any case, by the time the Commonwealth of Massachusetts had formally taken the Dugmar property — on Sept., 15, 1933, by eminent domain — Duggan and Mahar had naively or shrewdly (take your pick) drawn up an 800-lot subdivision plan for their property. A “gentlemen’s estate”, they called it — with “beach access,” for they had secured access to Curtis Pond and harbored visions, on paper at least, of selling these lake-front lots to Springfield swells in search of a holiday home.

As the creation of Quabbin Reservoir was going to happen after all, Duggan and Mahar sought “fair” compensation from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts — to the tune of $436,500, or some $9.5 million in 2022 dollars.

For the record, the town of Greenwich in its entirety had last been assessed, in 1932, at $640,000.

The state, which valued the golf property at no more than $56,000 — basically, a sum of the club’s biggest assets, plus maintenance equipment and whatnot — immediately balked at Duggan and Mahar’s asking price. The matter was referred to a Board of Referees, a body specially appointed by Quabbin’s administrative entity, the Metropolitan District Water Commission, to arbitrate disputes such as this. At first the Referees awarded Duggan and Mahar a split-the-difference sum of $221,000, pending approval by the state Supreme Court. The court would offer no such approval; it remanded the matter to the Referees.

Determining fair market value for Dugmar Golf Club — at the time of its “taking” in 1933 — would prove an arduous task. The legal process took nearly four years and produced some gloriously arcane golf course-related testimony. An endless parade of real estate experts took the stand, but so did an assembly of New England golf luminaries, all of whom offered their varying opinions on the quality (read: ultimate monetary value) of Dugmar.

Appearing for the state, among others, were Walter Hatch, longtime construction superintendent in the employ of Donald Ross; Fred Wright, a 1923 Walker Cupper and 7-time Massachusetts Amateur champion; and Dr. Lawrence S. Dickinson, distinguished agronomist and longtime member of the faculty at the University of Massachusetts in nearby Amherst. Produced by the Commonwealth to argue for Dugmar’s lower valuation, Dickinson was particularly critical of the property’s soil — several samples of which he brought to the Springfield District Courthouse in masonry jars.

Appearing for Duggan and Mahar were Orrin Smith and fellow architect Wayne Stiles, both of whom offered testimony well ahead of their times. For instance, while the nine holes themselves were built for $18,000, the architects testified, Dugmar’s golf course actually increased the value of the property around it, including these would-be housing units. Similar arguments would be trotted out for several decades to come, only to be shorn of currency and credence following the Great Recession of 2008, from which golf-related real estate values have never fully recovered.

Assistant Attorney General John S. Derham, a bombastic figure of the non-golfing variety, wasn’t buying any of this conjecture. At one stage, he pointedly asked Stiles whether it was “good architecture” to place larger greens on holes requiring a long approach and smaller greens where only a short carry is necessary. “Any fool knows that,” snapped the architect — or so reported the Springfield Evening Republican, which doggedly covered the hearings from start to finish.

Long story short, the state’s witnesses agreed that Dugmar was worth anywhere between $52,000 and $56,000. Duggan and Mahar’s cadre of specialists all agreed the property was worth between $340,000 and $360,000, mainly on account of all the house lots they might have sold.

In the end, on June 11, 1937, the Board of Referees ruled that Duggan and Mahar be awarded $150,000 for their condemned property, plus 4 percent interest accrued from the land-taking in September 1933. That brought the total payout, including legal and court fees, to $179,042.

Not bad return for a disposable item.

Ultimately, Duggan and Mahar received more than $1,100 per acre for Dugmar GC. On average, Greene asserts, other landowners in the Swift River Valley towns of Dana, Prescott, Enfield and Greenwich were compensated at approximately $100 per acre. Contemporary press accounts in the Athol Transcript described Duggan and Mahar as “aggressive, up-to-date businessmen”, and so they were. It took a while, but eventually they beat the state at its own game — in its own eminent backyard.

•••

Once the judgment was handed down, Dugmar GC beat a hasty retreat into the deeper recesses of public consciousness. Our Chapman Valve executives picked up and left Greenwich in 1933, content to pursue their Dugmar concerns in court. The putting greens, if Stanley Mega is to be believed, were uprooted and sold, perhaps to some long-admiring greenkeeper at a nearby course. “When did the course close for good?” Greene asks rhetorically. “We have reports of people playing there well after it had been abandoned, in 1933. But other than that, we don’t really know.”

One thing’s for sure: the water started rising on Aug. 14, 1939. By that time Dugmar GC had been disposed of.

Mahar didn’t long enjoy his share of the $179,042. He died of a massive cerebral hemorrhage just six weeks after the judgment came down. He was 52 years old. Duggan lived a while longer, became a member of Longmeadow and Springfield country clubs, succeeded Mahar as president of Chapman Valve, and made a name for himself as a philanthropist and Democratic Party bigwig, though he never stood for office. He too suffered a debilitating cerebral hemorrhage, in 1953, and died a year later at the age of 65.

The Quabbin Reservoir project was originally budgeted at $65 million and, amazing though it may seem to educated observers of Massachusetts’ infamous public works scene, the job was completed under budget — for a mere $54 million, thanks to depressed labor costs and federal grants. “So, paying Duggan and Mahar was a drop in the bucket,” Greene notes. “Even so, that was taxpayer money. Their attitude was, ‘We’ll do this, have a good time and if things work out, we’ll make some money on it.’ ”

And so they did. Duggan and Mahar even managed to fashion a lasting, relatively dry testament to themselves and their anomalous, dually eponymous endeavor: The fieldstone lodge on Curtis Hill still stands — on the south-facing shore of what became Curtis Island. It remains the only man-made structure, the only above-water evidence of The Lost Towns in the entire 89-square-mile Quabbin reserve.

“I find that extremely ironic,” says Greene, “because here’s something that was built by outsiders — and it was one of the very last things ever built in the valley. It’s really quite a monument.”

To what exactly?

“To the cupidity of Duggan and Mahar.”

•••

Biologist and scuba enthusiast Dr. Ed Klekowski is way into pre-pollution fauna, which explains why, for years, he had tried to get a close, forensic look at the Quabbin’s floor — to study the organic legacies of lakes and streams long ago overwhelmed by 412 billion gallons of river water. Several years ago, he succeeded. Klekowski led a dive of the area during the 2001 filming of “Under Quabbin”, a Massachusetts public television documentary which chronicled the lives of humans (and pre-pollution fauna) in the Lost Towns. This makes Klekowski, his cameramen, and their guides in the Massachusetts State Police Underwater Recovery Team the last people to see Dugmar Golf Club up close.

“Diving the golf course was much more interesting to think about than actually do,” reports Klekowski, a professor of biology at UMass Amherst. “Flooded fairways are probably the planet’s most monotonous dive sites: endless vistas of algae-covered flatness! We spent most of our time searching for something, anything, to film. Golf will never be an underwater sport.”

Klekowski’s team did find several of Dugmar’s irrigation pipes protruding from what is now the reservoir floor, in addition to the stone patio Duggan and Mahar had built beside the old farmhouse where, six decades earlier, martinis had been served (despite federal law) and beknickered sportsmen (despite their marital status) had flirted with flappers. “Our goal,” Klekowski says, “was to find and video the remains of the buildings associated with the course. When we finally found the old foundations, you couldn’t but feel a bit nostalgic. It was actually sort of creepy being down there, where there had been so much life at one time.”

It’s illegal to set foot on Curtis Island today, but Bradley Gage has done it. Twenty years ago, as a member of the state Fisheries and Wildlife Board, he and his fellow board members lunched there. It was an odd homecoming for Gage who was born in nearby Enfield — some 40 feet down and two miles north. He spent the first 8 years of his life there before his father, Roy, moved the family to Amherst in 1932.

“My dad played Dugmar,” Gage says. “He talked about it with pride and interest, that he and his friends had played it.” Gage had been too young to have experienced the course himself, to remember much of anything about the place. But he grew up to become a golfer and Gage wishes he had talked more of Dugmar with his dad, while they could have. It’s a false memory he wishes he had cultivated further — because some memories are worth having, even if they’re not one’s own.

They are complicated things, these memories. Stanley Mega retains many of his own, but they can prove a burden. It had been 30 years since Mega had spoken or thought of Dugmar Golf Club, he says, and one could see the act — exhilarating for a time — eventually led him back to the realities of an 85-year-old life. Mega doesn’t play much golf anymore. After 20 minutes of animated recollections his voice trailed off in that way an older man’s sometimes does. His brother is gone now. So are Dave Belisle and Jimmy Fitzgerald. Whitey Wisniewski, too.

Dugmar GC may as well be gone. It exists only in the suspended, dreamy netherworld of algae, pre-pollution fauna and would-be tap water — utterly hidden from all those lacking scuba gear and a police escort. The train doesn’t stop in Bondsville or Greenwich any longer. Route 21 survives, but only in part. The road terminates outside Belchertown, the asphalt ribbon slowly descending toward, then disappearing into the Quabbin with an eerie finality.

The stone patio beside the converted farmhouse is the only underwater evidence that Dugmar GC was ever there.

Comments ( 5 )