Harold Gardner Phillips, Jr., 1936-2011

So my dad, who died almost exactly one year ago, was a pretty serious pack rat. He didn’t really save things with any kind of direction. It was more or less an involuntary urge he had (and one I happen to share). Some of us simply cannot countenance the idea of parting with something that, at one time, meant something to him or provided her lasting joy, or insight. At some point my mother threw away a pair of sweatpants my dad had worn in college. This was the source of playful recriminations for years to come. Books were something never to be discarded and while he quite avidly lent them out, he wanted them back. The man passed from this Earth with at least 40 programs on his TiVo, all of which he’d seen but for some reason felt the need to archive.

I suppose that assembling these things, even as a sort of random catalogue (and holding them over time), does indicate direction. He would run across them randomly, on his own, and enjoy the memories. His wife and children might run across them, too, and their reports or remarks would bring it all rushing back to him yet another time.

My father was the first of our immediate family core to go, and so this is the first time our little unit has dealt with one of the five being permanently absent. Accordingly, there has been an active gathering and parsing of these trinkets, these literal souvenirs he left behind. We’ve paid special attention to these things, interpreting them in the context of this fellow we all knew so intimately.

Dad was a big golfer. The U.S. Amateur concluded last week and it was just the sort of televised sporting event he would have adored (see my account here). I’ve written about the golfing life my dad enjoyed, the subtext being that I wouldn’t have much of a golfing life without exposure and direction from his.

But it was ultimately his golfing life, not mine, just as the tiny, sleek, leather-detailed lighter — the one that sat unused in his top-left bureau drawer for decades — was his memento, reminiscent of a time he apparently wished to bank and recall. And maybe the lighter and all this other stuff had been meant for me or my brother, sister or mother to remember him by. During his last year, he passed to me the Johnny Hopp model baseball bat and first-baseman’s mitt he’d owned since he was a kid. Why else would he do something like that?

Among other things, there were several shoeboxes of stuff left behind when my dad, a firm atheist, left this mortal coil. There were big, substantial things, too, things the family reverently went through, remembering him and feeling sad about it, then dividing up so we might all have a healthy supply of these bits going forward.

But the smaller stuff fit into a few shoeboxes, and one was full of scorecards and other golf paraphernalia. Some of these items I had seen but very few of the scorecards were familiar. Here and in a few posts to come is a select accounting, because in the thousands of rounds he logged over seven decades, he only saw fit it to save these dozen or so. They must have meant something to him, and it seems fitting to pore over them and try to discern that something — along with other historical tidbits from his golfing life — on the first anniversary of his death.

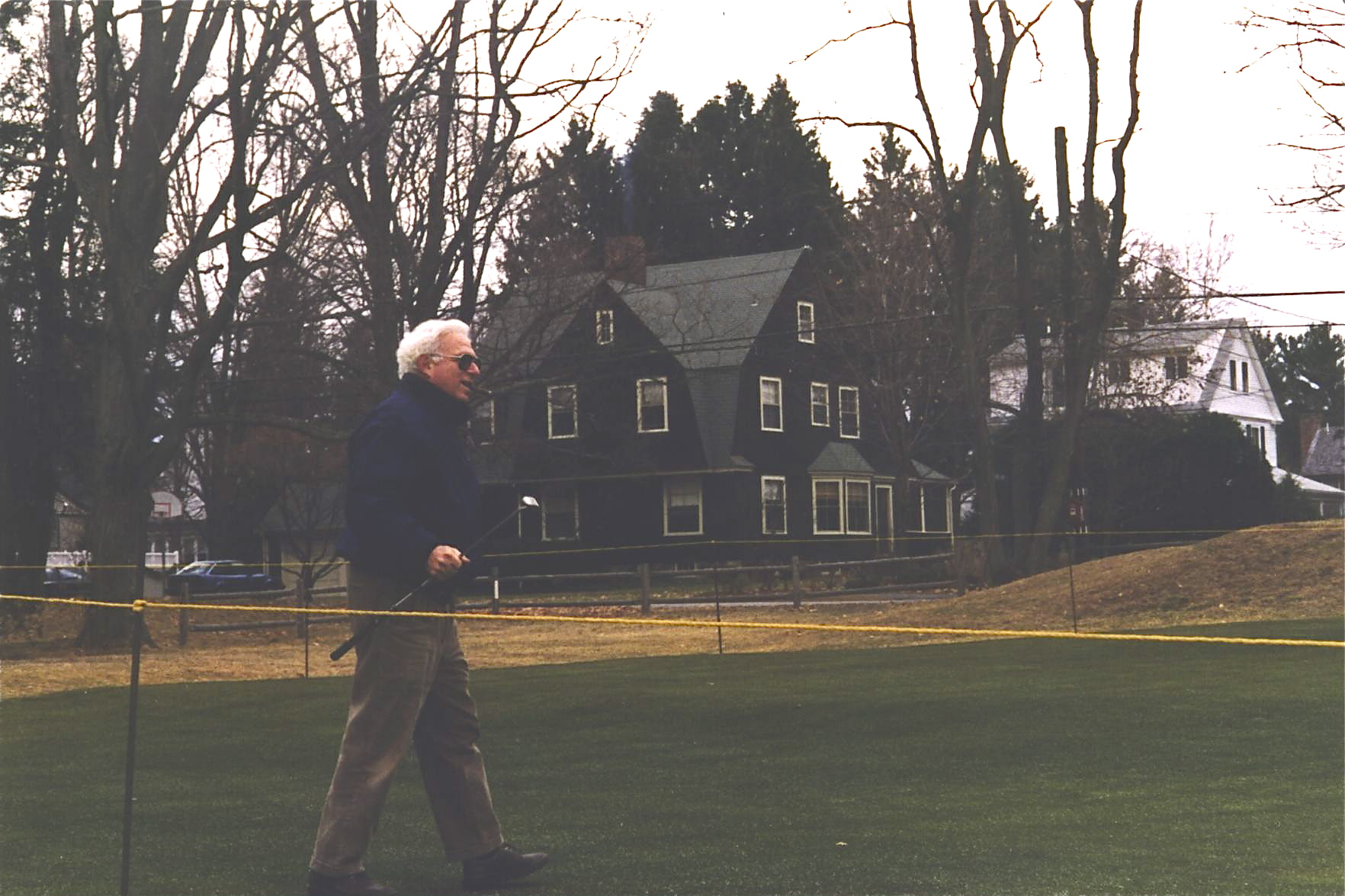

This shot of my dad as a young high schooler was taken some time contemporaneous with the round at Jumping Brook.

• Jumping Brook CC, Neptune, N.J., circa 1953: No date on this one. My dad seemed to date only the scores worth dating, and he shot another 84 here with a fellow named Jack Sax (which could be a shortened version of the guy’s full name; my dad refers to himself as Hal Phill; it’s definitely his writing). In 1953 my dad would have been 17 and you gotta figure he played this match as a member of the Red Bank High School golf team in the spring of 1953, before he went off to Lehigh as a freshman. I can pinpoint the date because Johnny Alberti is listed as the pro and he’s also mentioned in passing as being the pro at Jumping Brook in an October 1953 issue of Golfdom, the forebear of all golf trade journals. I edited one of its progeny, Golf Course News, in the ‘90s, and it was fascinating to read this compilation of golf news from all over the country, published as one continuous column for 20 pages! Every new pro and retired superintendent and new course rumor is granted a paragraph. At GCN, we’d have broken all this into 40 stories with their own headlines to make a new section, which probably would have gone on for 20 pages (!). The more things change… My dad was a Jersey guy. Raised on the shore in Little Silver, Long Branch and Red Bank; he and his family would ultimately make house in Montclair and Haddonfield, before moving more or less permanently to Massachusetts. My paternal grandparents were both keen golfers, members of the post-war, hyper assimilated Jewish middle class. When you’re aping WASPs, you play golf and they did honestly love it. They were members of Old Orchard Country Club, where my dad grew up playing and caddying, but they ventured out to places like Jumping Brook, Fort Monmouth and Canoe Brook. My grandfather, Poppy, was a member of Hollywood GC in nearby Deal sometime in the 1930s. He was a lefty and was, at times, a single-digit player himself, according to my dad. My Gram was a good athlete, a tennis player really but picked up golf to be more like Clare Booth Luce or maybe Martha Gellhorn. They arranged lesson for my dad with George Sullivan, the pro at Old Orchard, and off he went. He and another good player, Ronnie Choquette, actually formed the golf team at Red Bank High, if I’m not mistaken. I’m sorta hoping this was merely a casual round because poor Jack Sax shot 102. But the first three holes would seem to indicate a match underway, as there’s a +1, a +2, and +3 listed two rows below the scores. Upon examination, the card shows my dad winning the first 12 holes before halving the 13th, but it would appear he didn’t see the point in writing any of that down. I’ll do it, dad: You beat him 10 & 8.

• TPC Sawgrass, Ponte Vedra, Fla., circa 1983: I have no idea who these guys were my dad played with that day in north Florida: Emil, Pete (a 7 handicap apparently) and Dave. But I was certainly made aware of this round. “Hal” shot 82 from the blues and claimed 12 skins, though he and Dave lost the team match. My dad was playing off 12, or so says the card (this was probably some tournament connected to a convention held nearby; the scorecard is kept quite formally, in a way maybe an event administrator had requested; my dad certainly never scored in this sort of detail). This is a typical round from my dad when he was playing some pretty good, middle-aged golf. He sandbagged this a bit because he carried for years a steady 7-10 handicap at his home course, Nehoiden GC, across the street from our house in Wellesley, Mass., which was and remains a low-slope job, antique and tight, but a place you should score. But then my dad was, in a way, a true 12. He went to the TPC, site unseen, and shot 82. He could shoot 83-84 pretty much anywhere, which is a fairly rare gift… Like a lot of golfers in 1983, he was pretty gob-smacked by the golf course, Pete Dye’s breakthrough design in the flamboyant, post-modern, stadium-mounded links category. My dad was never a course-design freak, though he got into it more as I got into it more. [I presented him at one point, years later, a signed first edition of Tom Doak’s “Confidential Guide”, wherein the architect — long before he became the It Boy of Minimalist Design — lavishes praise and shits upon, by turn, a laudably wide-ranging assemblage of the courses he’s played. It’s some of the best bathroom reading ever devised, and I mean that as an unalloyed compliment. These editions are rare and sought after these days, though my dad never really grasped the import of having one. Now I’ve got his copy back. Then both burned in a 2016 barn/office fire.] The TPC Sawgrass clearly made an impression on him, and I think that (and the course’s subsequent notoriety) moved him to keep this scorecard. When my dad played a golf course that, for good or ill, either confused or radically challenged his expectations, he wasn’t always eloquent in explaining his views. He would assess it as “sorta kooky” or “a little weird”, then close the thought with a mildly exasperated cackle.