It’s often argued that the 1975 World Series — contested 50 years ago this month — ranks among the finest in baseball history. In terms of legendary personalities and the competitive iconography that framed them, Game 6 featured enough fairy-tale moments all on its own: a not-yet-befouled Pete Rose bellyflopping into third then popping up to jawbone with his opposite number, Rico Petrocelli; rookie golden boy Fred Lynn propped limp and lifeless against the center-field wall after failing to flag down Ken Griffey’s RBI triple in the 3rd; Sparky Anderson on the top step of the dugout, ready to give Rawley Eastwick his trademark hook, only to let him face Bernie Carbo in the 8th; Johnny Bench short-hopping George Foster’s throw from left-field foul territory to cut down Denny Doyle at the plate, sending the game to extra innings where, of course, Carlton Fisk waved his game-winning homer just fair enough to hit the foul pole.

Taken together, those 12 innings form a universe unto itself, an heroic parade of Hall of Fame and otherwise iconic players doing impossibly dramatic things under extraordinary circumstances.

As a result, however, Game 6 also tends to overshadow what made this 7-game encounter an all-timer. This past summer I happened upon a passing reference to Luis Tiant’s epic 163-pitch, complete game performance in Game 4. I grew up in Boston and turned 11 the month before this World Series took place. I watched every second of Game 4. To my shame, apart from El Tiante running the bases in his little blue jacket, I remembered very few specifics.

Friend, let me remind you that for all its faults, the 21st century is a remarkable thing: All seven installments of this Fall Classic are available via YouTube — in their entirety, without commercials — so I watched Game 4 on my iPhone over the course of several hours in July. This sublime experience led to web-aided consumption of Games 2 and 3, in that order, as these, I reasoned, were the chapters in this epic saga that I remembered least of all.

I undertook this throwback-baseball immersion exercise at the same time I was reading Chuck Klosterman’s fine non-fiction book, “The Nineties,” wherein he posits that October 1975 was also a critical tipping point — those final cultural moments where baseball and its fans could claim “the sport held a unique place in U.S. life and would always be recognized as the national pastime.” By 1990, he points out, twice as many people watched NFL football.

Four years later, with release of his mini-series Baseball, Ken Burns presented the game as a prism through which we might better understand the American experience. A soulful, often convincing take but an excuse for the historian to treat the game like a relic, an historical phenomenon that did what it did but had since relinquished much of its civilizational juice.

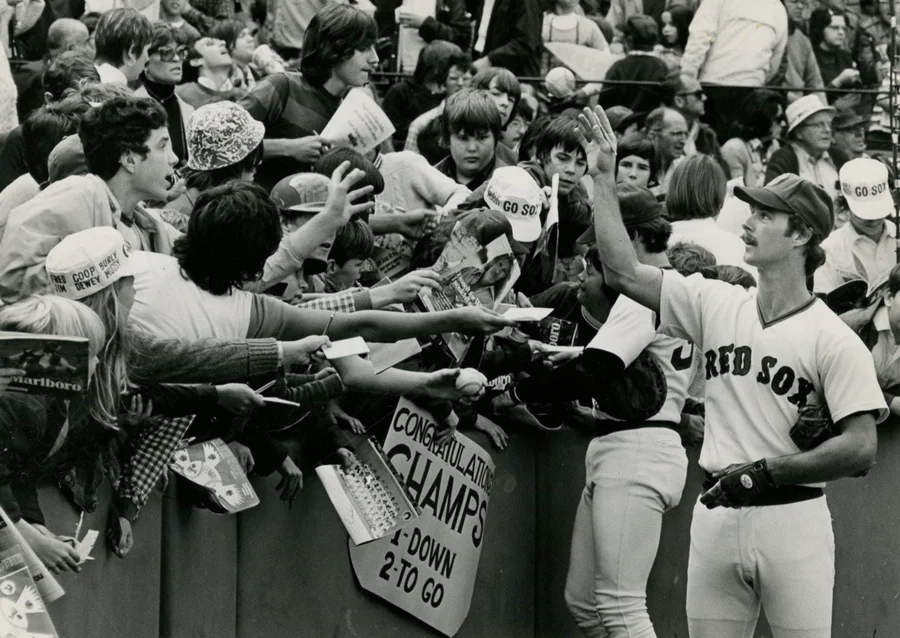

So much of the American social contract came undone during the Seventies, why should baseball have been exempt? If retroactive understanding recasts the 1975 Fall Classic as a swan song, so be it. However, allowing such a raft of perfectly amazing memories to fall through the cracks unheeded and under-absorbed — when they’re all just sitting there on some Google server, waiting to be enjoyed all over again — is foolish. What follows is a YouTube-enabled report on this 3-game series within a Series, an event I first consumed as pre-teen, staying up way past my bedtime, exulting and sobbing by turn in a suburban living room exactly 13 miles southwest of Fenway Park.

•••

Game 4, Riverfront Stadium, Oct. 15, 1975

El Tiante was already a Boston legend before he took the mound in Game 4, of coursre. After doing his best to thwart Sox hopes in 1967, for Cleveland (one of four clubs with legitimate pennant hopes that final weekend of the season), he’d come over in 1971 and immediately claimed our hearts. No one knew how old this amiable, rather elfin Cuban really was; I suppose we still don’t know. He was a bit dumpy and could come off as clownish though a lot of that public persona was surely down to his idiosyncratic grasp of English. But he won — 18 times in 1975, despite back issues — and he did so with singular style. After his virtuoso performance in Game 4, his place in the Boston Sports Pantheon was utterly secure.

The Reds had jumped out to a 2-0 lead, but starter Fred Norman surrendered 5 in the 4th and that’s all Tiant would need, throwing ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY-THREE pitches to level the Series and nail down another complete-game victory, 5-4.

Yet that’s mere box-score fodder. Tiant at his best had to be observed to be fully appreciated, and he proved even more indomitable 50 years on, despite my diminutive screen. While the man had shut out the Reds in Game 1 at Fenway four days earlier, familiarity helped the National League champions not a whit. Tiant bullied and confounded them by turn — nearly picking the imperious Joe Morgan off first in the 7th, twice running the bases, scoring what proved to be the winning run, and looking utterly gnomish the entire time.