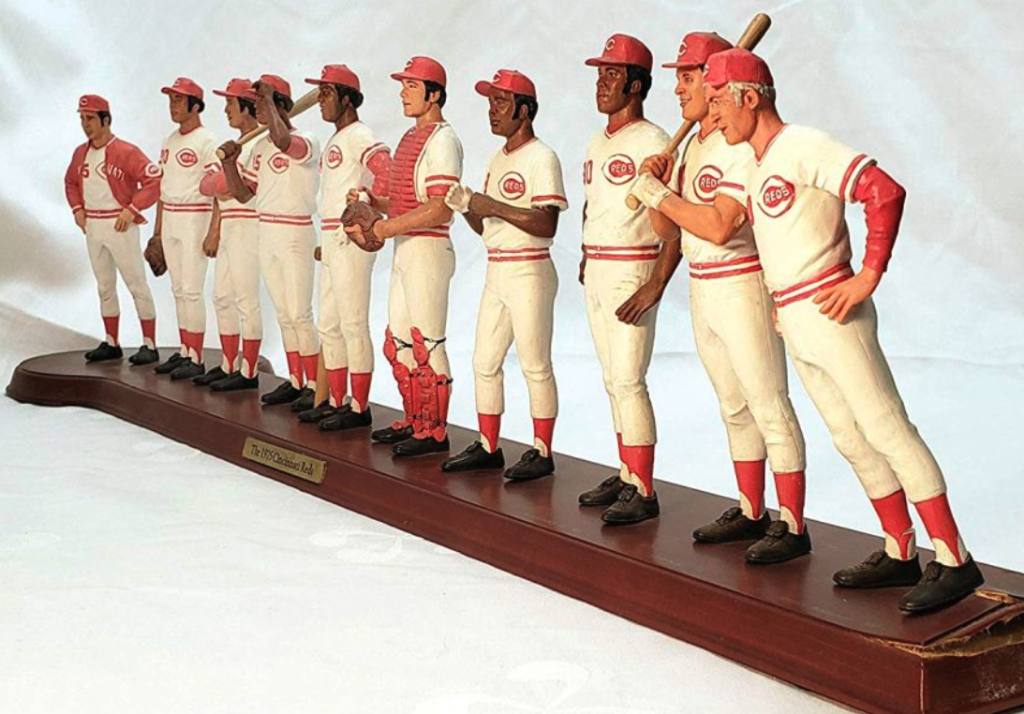

It’s often argued that the 1975 World Series — contested 50 years ago this month — ranks among the finest in baseball history. In terms of legendary personalities and the competitive iconography that framed them, Game 6 featured enough fairy-tale moments all on its own: a not-yet-befouled Pete Rose bellyflopping into third then popping up to jawbone with his opposite number, Rico Petrocelli; rookie golden boy Fred Lynn propped limp and lifeless against the center-field wall after failing to flag down Ken Griffey’s RBI triple in the 3rd; Sparky Anderson on the top step of the dugout, ready to give Rawley Eastwick his trademark hook, only to let him face Bernie Carbo in the 8th; Johnny Bench short-hopping George Foster’s throw from left-field foul territory to cut down Denny Doyle at the plate, sending the game to extra innings where, of course, Carlton Fisk waved his game-winning homer just fair enough to hit the foul pole.

Taken together, those 12 innings form a universe unto itself, an heroic parade of Hall of Fame and otherwise iconic players doing impossibly dramatic things under extraordinary circumstances.

As a result, however, Game 6 also tends to overshadow what made this 7-game encounter an all-timer. This past summer I happened upon a passing reference to Luis Tiant’s epic 163-pitch, complete game performance in Game 4. I grew up in Boston and turned 11 the month before this World Series took place. I watched every second of Game 4. To my shame, apart from El Tiante running the bases in his little blue jacket, I remembered very few specifics.

Friend, let me remind you that for all its faults, the 21st century is a remarkable thing: All seven installments of this Fall Classic are available via YouTube — in their entirety, without commercials — so I watched Game 4 on my iPhone over the course of several hours in July. This sublime experience led to web-aided consumption of Games 2 and 3, in that order, as these, I reasoned, were the chapters in this epic saga that I remembered least of all.

I undertook this throwback-baseball immersion exercise at the same time I was reading Chuck Klosterman’s fine non-fiction book, “The Nineties,” wherein he posits that October 1975 was also a critical tipping point — those final cultural moments where baseball and its fans could claim “the sport held a unique place in U.S. life and would always be recognized as the national pastime.” By 1990, he points out, twice as many people watched NFL football.

Four years later, with release of his mini-series Baseball, Ken Burns presented the game as a prism through which we might better understand the American experience. A soulful, often convincing take but an excuse for the historian to treat the game like a relic, an historical phenomenon that did what it did but had since relinquished much of its civilizational juice.

So much of the American social contract came undone during the Seventies, why should baseball have been exempt? If retroactive understanding recasts the 1975 Fall Classic as a swan song, so be it. However, allowing such a raft of perfectly amazing memories to fall through the cracks unheeded and under-absorbed — when they’re all just sitting there on some Google server, waiting to be enjoyed all over again — is foolish. What follows is a YouTube-enabled report on this 3-game series within a Series, an event I first consumed as pre-teen, staying up way past my bedtime, exulting and sobbing by turn in a suburban living room exactly 13 miles southwest of Fenway Park.

•••

Game 4, Riverfront Stadium, Oct. 15, 1975

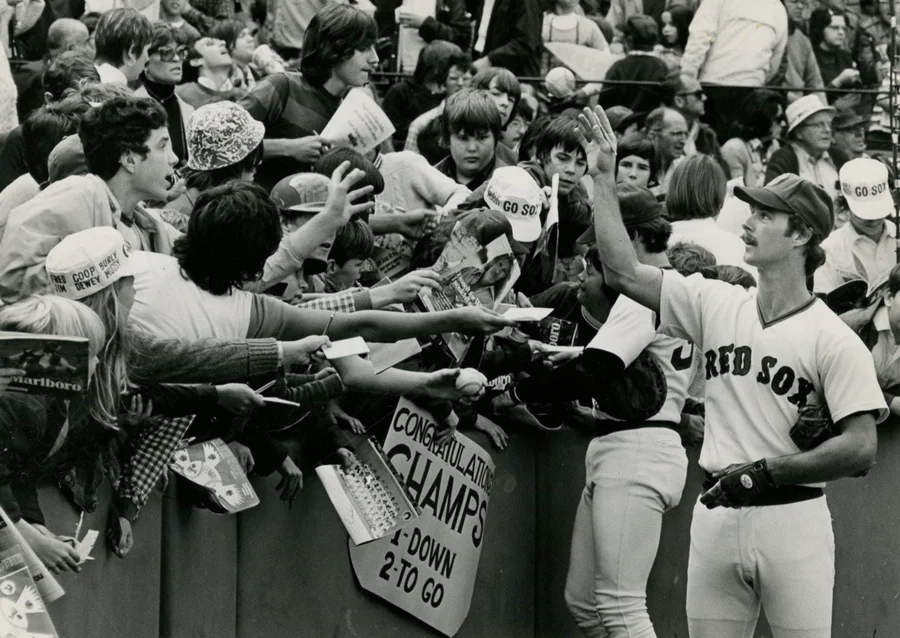

El Tiante was already a Boston legend before he took the mound in Game 4, of coursre. After doing his best to thwart Sox hopes in 1967, for Cleveland (one of four clubs with legitimate pennant hopes that final weekend of the season), he’d come over in 1971 and immediately claimed our hearts. No one knew how old this amiable, rather elfin Cuban really was; I suppose we still don’t know. He was a bit dumpy and could come off as clownish though a lot of that public persona was surely down to his idiosyncratic grasp of English. But he won — 18 times in 1975, despite back issues — and he did so with singular style. After his virtuoso performance in Game 4, his place in the Boston Sports Pantheon was utterly secure.

The Reds had jumped out to a 2-0 lead, but starter Fred Norman surrendered 5 in the 4th and that’s all Tiant would need, throwing ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY-THREE pitches to level the Series and nail down another complete-game victory, 5-4.

Yet that’s mere box-score fodder. Tiant at his best had to be observed to be fully appreciated, and he proved even more indomitable 50 years on, despite my diminutive screen. While the man had shut out the Reds in Game 1 at Fenway four days earlier, familiarity helped the National League champions not a whit. Tiant bullied and confounded them by turn — nearly picking the imperious Joe Morgan off first in the 7th, twice running the bases, scoring what proved to be the winning run, and looking utterly gnomish the entire time.

In the 8th, 150 pitches into the biggest game of a 19-year MLB career, he shifted his wind-up into full-on baroque mode. This was something the portly righthander did with nobody on and only when the moment required — fully turning his back to the plate and bobbing his head before wheeling toward the batter, only to deliver the ball from one of four different arm positions.

This was the pitching motion every Bostonian boy mimicked during the summer of 1975. I still have it down pat, every last detail (having first adapted it for Whiffle Ball use). When the Red Sox finally come calling, looking for some schmuck to throw out a ceremonial first pitch prior to a meaningless June game vs. the Twins, I’ll be ready. All the 60something dudes in the crowd that blessed day will surely go wild.

Other Game 4 observations:

- NBC aired the ‘75 Series and Game 4 featured the still-familiar broadcast team of Joe Garagiola and Tony Kubek — joined in the booth by legendary Reds announcer Marty Brennaman, who was consulted on various Cincy-centric matters over the first 4 innings before taking over the play-by-play. At one point, the trio noticed that below the 330-foot marker, on the left field wall, it also read 100.58 — as in meters. Brennaman explained that the digits had been there since Riverfront opened in 1970, then went on to casually mock the metric system before making some remark about the seating habits of Alex Grammas, Sparky Anderson’s bench coach. Folks of my vintage will recall concerted, public school-led efforts to teach us the metric system during the mid-1970s. Its adoption was inevitable, they told us.

- Down 2 games to 1 and in need of a spark, Sox Manager Darrell Johnson started the not-quite-immortal Juan Beniquez. He led off and played left field in Game 4, moving Carl Yastrzemski to first base. By 1975, I was 3 years into serious baseball-card collection and the Sox had been gathering superb young talent all the while. Back then I knew everyone in both leagues, let alone the Red Sox roster — but I had frankly forgotten that Juan fuckin’ Beniquez played any role in this series. My first glimpse of Juan via YouTube — his Latin afro bulging out from under his batting helmet — warmed the cockles of my heart. The Puerto Rican native was quiet in Game 4 but went a creditaable 8 for 27 in this series with 4 runs scored and 3 RBI.

- Yaz played first and was his usual playoff self: on base 3 times, with an RBI. His signature batting stance was the one my friends and I mimicked most (I can still do that one, too). It always looked to me like he was swinging too big a bat, especially late in his career — out of sheer stubbornness.

- After his infamous pinch-hitting episode in Game 3, Reds utility man Ed Armbrister came up and successfully laid down a sacrifice bunt with the score tied in the 9th. I can remember thinking, back in 1975, that his reintroduction — some 24 hours after such blatant, public villainy — would prove a terrible omen. But with Cesar Geronimo now at second base, Tiant intentionally walked Pete Rose, retired Griffey on a liner to left and popped up Joe Morgan to send Reds fans home annoyed but impressed.

- Riverfront was equipped the worst sort of 70’s-era AstroTurf, but it never proved an issue in this game nor any of those played in Cincinnati. Indeed, Kubek relayed the fact that Sparky Anderson had been mighty impressed with the ground covered by Sox outfielders over the first three games: Dwight Evans in right, rookie Fred Lynn in center, and Beniquez in left (Yaz played left too, in Games 1, 2 and 3, replacing injured rookie sensation, Jim Rice). I’d never considered that Boston outfield to have possessed any sort of superior range, certainly not in comparison to the Reds outfield: Geronimo in center, Griffey in right and the relatively plodding George Foster in left. But who am I to argue with Sparky?

When Rico Petrocelli first came to bat in the 2nd inning of Game 4, NBC primitively superimposed his stats on the screen: He was already 7 for 12! Rico and Yaz were the only two holdovers from the ’67 Impossible Dream team; I had forgotten what a great series Rico played eight years on. That’s precisely when I resolved to watch Game 2 via YouTube, as well. The series opener had been a pitchers’ duel until Boston scored 6 runs in the 7th; Game 3 featured the infamous Armbrister Incident. By contrast, Game 2 remained a cypher so many years down the road. I didn’t even remember who started that game for the Sox … though I assumed it could only have been the inimitable Bill Lee.

•••

Game 2, Fenway Park, Oct. 12, 1975

Question: Why does one suppress a memory?

Answer: To avoid the pain.

Apart from who won, I had remembered almost nothing of Game 2, either. Watching it again via iPhone, I was reminded of just how tantalizingly close the Red Sox came to taking total command of this World Series — and why I had buried that disappointment so deep in my subconscious.

Bill Lee did indeed prove the tragic star of Game 2 and the main reason Boston should, by all rights, have taken a 2-0 lead to Cincinnati. A 17-game winner in 1975 (and ‘74, and ‘73), Lee was mesmerizing against the Big Red Machine, brazenly serving up a stupendous assortment of junk — looping eephus curves, standard curves, screwballs, change-ups — accented to great effect by three varieties of fastball. It wasn’t just the “stuff” he had (“He’s throwing everything up there but the rosin bag!” Garagiola mused in the 6th), but his speed and efficiency. Lee worked fast even by 1975 standards and didn’t nibble; he threw that junk over the plate and basically dared the Reds to hit it. By and large, they couldn’t. Not squarely. I’ve searched high and low for Lee’s Game 2 pitch count, the exact number of deliveries he used in holding Cincinnati to 1 run and 5 hits over 8-plus innings. To no avail. They didn’t talk about nor diligently record such things back in 1975, apparently.

There was a rain delay after 8 innings of Game 2, though another online search to determine its duration also came up empty. YouTube editors clearly excised this down time from the recording, foiling the picklocks of SABRmetricians and conspiracy theorists. (Allow me to advance here the Nixonian idea that 18 minutes of that game tape were mysteriously erased — and not by accident!)

The Game 2 announcers mention the delay in passing as Lee bounds up and out of the dugout to pitch the 9th, a mass of sand/kitty litter mixture spread about the mound and plate areas. Three outs from a 2-1 victory and seemingly unaffected, Lee got ahead of the lead-off hitter, Johnny Bench, but Fisk’s all-world doppelganger doubled to right and the Spaceman was lifted. Dick Drago came on and pitched well, inducing a weakly hit ground-out (Bench to third) and popping up George Foster. Dave Concepcion beat out an infield hit to tie the game, stole second on a very close play, and scored the winning run on a double off the Monster by Ken Griffey.

Just like that, the game was lost and the Series tied.

Other observations:

- Cecil Cooper made the final out in a quiet Sox 9th. He started the game, played first and led off, as he had in Game 1. Or so I was reminded by Ned Martin, who sat in with the NBC broadcast team, as Brennaman had — or would — when the series shifted to Cincinnati. Cooper hit .311 that 1975 regular season, in a limited role. The year before, he looked like the Sox first baseman of the future, only for Rice to emerge and move Yaz to first. Coop would go on to become a truly great hitter only after Boston traded him to Milwaukee, in 1977, for the immortal George Scott.

- Coop swung at absolutely everything in this Series; but then, most everyone in either lineup did. It was striking to see so few pitches taken, so little “working the count”, as batters do so assiduously today. Bill Lee accentuated the impression by throwing so many strikes, but pitchers back then generally worked faster and more often threw the ball over the plate, another shocker for the 21st century viewer. Of the seven games played in this series, none but the extra-inning Game 3 and the epic 12-inning Game 6 extended beyond the 3-hour mark.

- NBC’s archaic graphics in Game 2 informed the viewer that Sox manager Darrell Johnson had played for the pennant-winning 1961 Reds, who were summarily boned and gutted by the Yankees in the World Series. I was merely reminded of this factoid because owning every last 1975 Topps baseball card, for both leagues, meant owning manager cards, as well.

- From the Dept. of Mispent Youth: During the 1970s, hydration was not yet a thing, so we spent gobs of money and acquisitive energy on other things — like Wacky Packs, cards and stickers sold in a baseball-card format (meaning: they came with gum) and featuring fake, often gross-out spoofs of familiar household products and brands. Like Hostage cupcakes, or Crust We found Wacky Packs altogether hilarious and attractively subversive. They were much the rage among preteen consumers during a brief period mid-decade — an era of notable junk food innovation. Pringles, Starburst and Skittles all debuted or otherwise became available at this time. When Frito-Lay introduced nacho cheese Doritos (1972), it blew our white-bread suburban minds.

- Dwight Evans didn’t do much in Game 2, though I was struck by how plain and conventional his batting stance remained in 1975, just his third full season in the Majors. Dewey would go on to enjoy a long career marked by the deployment of some truly bizarre plate mannerisms — many of them concocted under the tutelage of Sox batting coach/guru Walt Hriniak (1977-89). Some believe Evans should be in the Hall of Fame; none other than Bill James makes that argument. Having watched his entire 21-year run, and seen him suffer through some long, truly agonizing slumps, that seems to me a stretch. He was clearly one of the finest right-fielders of his era but that particular cohort (Dave Winfield, Cesar Cedeno, the recently departed Dave Parker) wasn’t so hot.

While I watched this game in fits and starts over the course of two days, I did manage to meaningfully luxuriate in the dulcet tones of Ned Martin, who taught me more about baseball than anyone else during the 1970s. It’s all a bit fuzzy now, in retrospect, because Ned would ultimately move to television (Channel 38 in Boston), a transition he may well have made by October of 1975. But I remember him equally well for his sterling radio work with partner Jim Woods. I had a clock radio in my bedroom growing up; it featured an old-fashioned radial dial with a scratch mark to indicate exactly where I could find Sox games on WHDH 850. Hearing Ned call Game 2 from the grave (he passed away in 2002) was a transcendent experience that honestly choked me up a couple times. Laying down on my bed, I eventually set the iPhone flat on my chest. The pictures rendered utterly secondary, I drifted off to sleep — as I’d done so many times when the Sox of my youth played on the West Coast.

•••

If Game 6 has become the de facto emblem of this World Series, it’s easy to understand why. Fisk’s homer in particular has evolved into a sort of shorthand for the grandeur and innocence of Major League Baseball prior to the profligacy of free agency and the ubiquity of MLB on cable.

Even if details of the other six games are little explored, folks do seem to understand that the ’75 Series shined a competitive spotlight on an extraordinary number of outsized baseball personalities — six Hall of Famers in total, with another, Pete Rose, recently made posthumously eligible. I mean, Jim Rice didn’t even play on account of injury. Ken Griffey is not in the Hall of Fame but could have been the Series MVP. George Foster does not reside for all time in Cooperstown, nor does Fred Lynn, but each was entering his prime in October 1975. Foster won the National League MVP two years later.

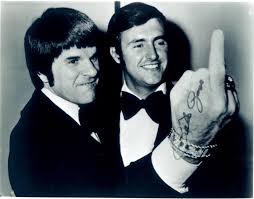

This particular series also helped cement in the public consciousness the reputations of two monumental figures.

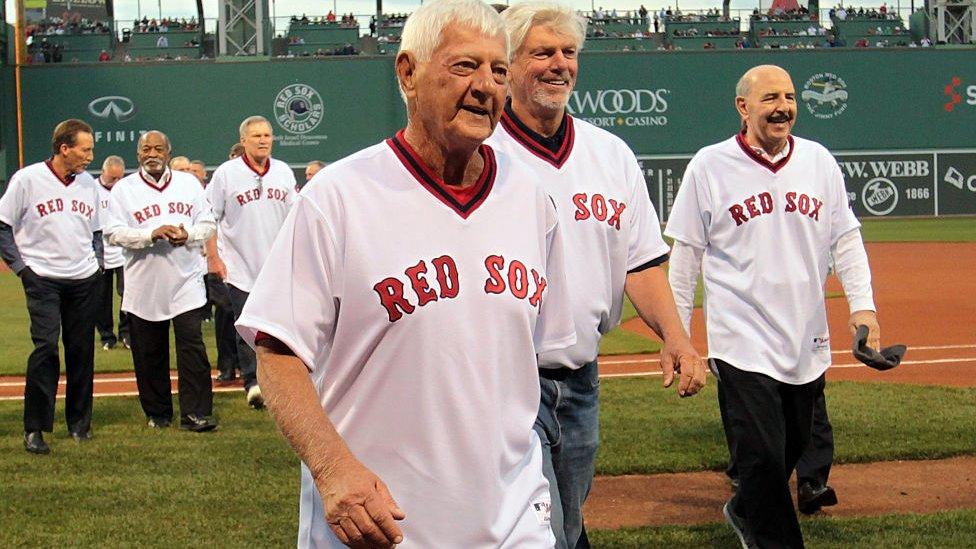

The first was Carl Yastrzemski, about whom both Roger Angell — the finest writer of baseball prose to have ever walked the earth — and former U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky were still rhapsodizing 40 years after he retired. I don’t hold myself in that sort of literary company. What’s more, having moved to Greater Boston in 1972, I was five years late to the Impossible Dream party, the much-sentimentalized pennant-winning season that coincided with Yastrzemski’s Triple Crown in 1967. Still, here are three things baseball fans might not realize about Yaz, and why he remains such a titanic and complicated figure.

- His Triple Crown season was not his best in the Majors. Yaz won three battle titles but lost a fourth to Alex Johnson by mere percentage points in 1970, when many argue he posted the finest statistical performance of his career. Just a single season separated 1970 from 1968, when Major League Baseball raised the mound and ushered in an era of pitching dominance (Yaz would repeat as AL batting champ in 1968, hitting a measly .301). By 1970, batting figures remained depressed across the board. Yet Yaz hit a career-best .329 that year, with 40 homers, 102 RBI and a career-best 128 walks, enabling a sterling on-base percentage of .452. He threw in 23 stolen bases just for the fuck of it. 1967 v. 1970: This was the debate we Massholes had, as kids, referring to the back of baseball cards. It’s a quarrel made even more interesting today by the plethora of “new” stats (check out the full monty here), which tend to favor 1967 — but fail to take into account the mound.

- As good as peak Yastrzemski was at the plate — and most all-around statistical analyses place him about #20 on the various all-time lists — he was a defensive player of comparable greatness. Of the 30 or 40 ballplayers ranked alongside Yaz via these various batting metrics, only a handful can claim this sort of elite duality: Willie Mays, Honus Wagner, Tris Speaker, Eddie Collins and Mike Schmidt. Plenty of others were fine fielders (Stan Musial, Rickey Henderson, Lou Gehrig, Eddie Matthews, Alex Rodriguez), but Yaz was the bestleftfielder in the American League for a decade or more. By 1974, he had moved to first base permanently, in addition to DH, to accommodate Cecil Cooper, then Jim Rice. In September 1975, with the Sox closing in on their first post-season appearance since ‘67, Rice broke his wrist. Captain Carl went back to left and there, for the first time in my experience, was the fielder everyone had raved about. Incredible arm, savvy and range, even in his dotage. Check out this down-gunning of Reggie Jackson during the 1975 ALCS. Go Google his catch during the 1969 All-Star game, or watch this stunner, which preserved Billy Rohr’s no-hitter. And, of course, no one played the Green Monster better. Yaz would go back to left for 152 games in 1977 — as a 37-year-old. He won another Gold Glove, his 7th.

- For all these achievements, however, and for the high esteem in which Carl Yastrzemski is still held throughout New England, the man remains a tragic figure. Twice during the mid-1970s, with the Sox on the brink of that elusive championship, it was the stoic, ever-taciturn Yaz who stood at the plate when the curtain came down. He closed the infamous ’78 playoff game against the Yankees, popping out to third baseman Craig Nettles — stranding both the tying and go-ahead runs. Yaz also made the final out in 1975, flying out to Cesar Geronimo in left center with Boston trailing by a run.

This not to say that Yaz wasn’t at his very best when Boston needed him most, because he generally was: He hit .400 in the 7-game Series loss to St. Louis in ’67, .455 against the World Champion A’s in the ’75 ALCS, and .310 against the Reds. No Red Sock was on base more often or scored more runs (7) during this World Series. Through 8 innings of the ’78 playoff game, perhaps the most soul-crushing moment of my entire childhood, Yastrzemski was immense — homering off the nearly unhittable Ron Guidry in the second inning and driving in another run in the 8th.

The indignity of twice making the final out — after having done so much — cannot be described as failure. It is a textbook example of tragedy. And texture.

By contrast, Joe Morgan used the 1975 post-season to stake his claim as the finest second baseman of all time. Despite coming up in 1963 and not winning a damn thing for 12 years, this Series pegged him as a “winner” and a thoroughly modern figure. Fleet of foot, he also hit with power — something second basemen didn’t traditionally do. Morgan took pitches and worked counts when few major leaguers bothered with such things. He led the league in walks four times and finished top 5 in that category a jaw-dropping 18 times.

While Pete Rose was awarded the ’75 Series MVP, reaching base 15 times (but scoring only thrice), Morgan was the indispensable man for the Reds, not just this October but the next one, as well. For Boston fans, that was the clear takeaway. It was Morgan’s dying-quail to center that drove home the winning run in the 9th inning of Game 7. It was his canny, unassisted double play that won Game 3. Unlike Yaz, Morgan only burnished his standing in retirement: He spent 30 years broadcasting ballgames on major networks. Yaz, by contrast, went home to his potato farm on Long Island and disappeared. He’s still alive, though you wouldn’t know it.

That’s the narrow view. Chuck Klosterman broadens it by arguing the 1994 MLB work stoppage changed the way we think about historical baseball figures and events. That unseemly strike, which canceled an entire post-season, “represented the point where baseball’s past became more desirable than baseball’s future, an inversion that would never really reverse itself.” Hard to disagree with that take, especially as a Bostonian whose team has won five World Series since 2004.

Yet here I am — still fixated on the one we lost 50 years ago.

•••

Game 3, Riverfront Stadium, Oct. 14, 1975

In my vain attempt to determine how many pitches Bill Lee threw in Game 2, I naturally ran across the Spaceman’s recollections of that game and the Series. One thing Lee maintains emphatically into the modern day: “We were a better team than the Reds, we outscored them [30-29], and we outplayed them. In fact, we should have won that Series in six games.”

Lee remains a benignly psychotic, thoroughly entertaining figure who, in his dotage, has begun to repeat himself — like his schtick about sprinkling ganja on his flapjacks. But the man makes a fair point: Yes, these Reds are often ranked among the best teams of all-time; they won 108 regular-season games in 1975, swept the Yankees in 1976, gained but lost two more World Series during this era (1970, 1972), and contended for the NL pennant every year. They exhibited an uncanny resilience in ‘75, coming from behind to win Games 2 and 7 — each in the 9th…

But Boston was better. Any review of Game 3 on YouTube makes this much clear: The Sox could easily have won the first three games of this series. That they instead trailed 2 games to 1 when Tiant took the ball for Game 4 remains something of travesty.

Game 3 is overshadowed by the Armbrister Affair but this particular tilt had everything: a World Series-record six home runs, another 9th inning comeback — this one from the Sox — a desperate emptying of both bullpens, and one of the most controversial umpiring decisions in Major League Baseball history.

I’ll say this about home-plate umpire Larry Barnett’s decision not to call interference on Armbrister, whose sacrifice bunt in the 10th turned this remarkable contest on its head: First, I had forgotten this notorious non-call took place in extra innings — it really did decide the game. Second, NBC’s broadcasting trio (including Reds employee Brennaman) abandoned all objectivity in the ensuing chaos. All three thought it was clearly interference and said so. Here’s the play. Judge it for yourself.

Here’s how we got there:

- Gary Nolan and Rick Wise started Game 3. Watching the tape five decades later, I vividly recalled my 11-year-old anxiety regarding the decision to start the Wise, a steady, bespectacled, inning-eating veteran for whom Boston had traded Reggie Smith (and received Bernie Carbo) in 1973. Wise was capable — he won 19 times in ’75 — but the owlish righthander was a fly-ball pitcher who seemed to benefit unduly from Boston’s hyper-productive line-up that summer. He won a lot of 8-6 decisions. He lost 12 times. Against the Reds, he gave up three hits through four-plus innings — all of them home runs. By the time DJ lifted him with nobody out in the 5th, Boston trailed 5-1.

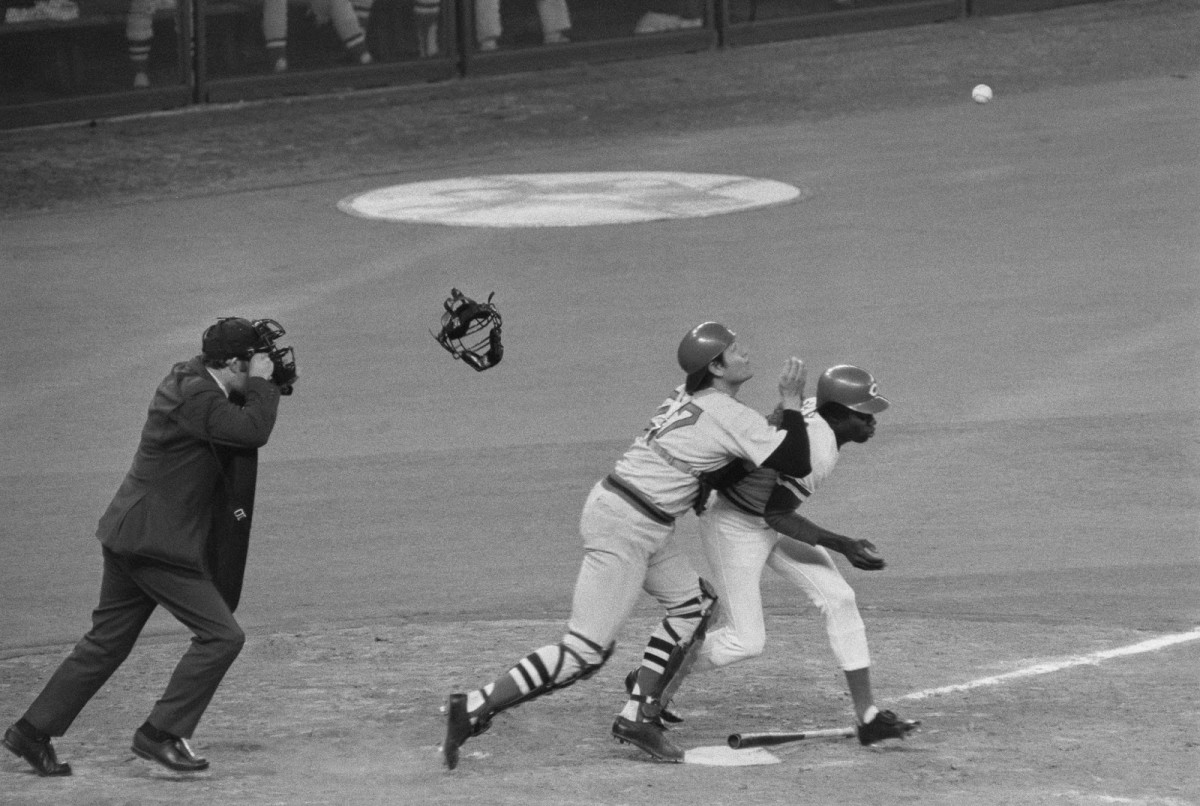

- This game was dingerfest. Fisk opened the scoring with a towering blast to left. Amazing to watch both Fisk and Bench during this series — arguably the two best catchers in baseball history, in their absolute primes. Bench answered with a tater of his own in the 4th.

- Carbo, who came up with the Reds, closed the gap to 5-3 with a pinch-hit homer in the 7th. It was later revealed that Bernie was high as a kite, on an assortment of Schedule 1 narcotics, when he cranked this and his more famous Game 6 home run. Dewey tied the game with a two-run shot in the 9th.

- The immortal, somewhat doughy Reggie Cleveland had pitched in superb relief of Wise until Carbo pinch-hit for him, to such great effect. Thereafter, Jim Willoughby held the Reds in complete check; he’d finish the series with an ERA of 0.00 over 6-plus innings, all in relief. Cleveland would end up starting Game 5, probably on the strength of this great relief outing. He got shelled.

- In the eventful 9th, once Evans had leveled things, the Rooster — Sox shortstop Rick Burleson — singled and the Mighty Reds fell into complete disarray. Sparky changed pitchers, again, and Johnson, with 1 out, chose to let Willoughby bunt instead of leaving advancement of the potential winning run to a more seasoned pinch hitter. Well, this obscure American League pitcher, who hadn’t batted all season, laid down the perfect sacrifice! At that moment in time, DJ had to be thinking that he was pushing ALL the right buttons… Alas, the ever-overeager Cooper popped up the first pitch and the inning was over.

- Still, to anyone who’d watched the arc of the first 9 innings, Game 3 had that unmistakable feel of something Cincinnati had squandered. In the bottom half of the 9th, Willoughby retired the Reds in order and second baseman Denny Doyle singled to lead off the 10th. By this time, Boston had outhit Cincinnati 10-5, erased a 5-1 deficit and demoralized the Reds bullpen. Yaz hit the next pitch to the wall, where Geronimo made a fine catch. Fisk walked to the plate and, once again, DJ did exactly the right thing — sending Doyle to stay out of the double play. But Fisk scorched one to second base where Morgan turned a perfect tag-and-throw, inning-ending double play.

- I had a good chuckle between innings when Fisk, who made the last out of the 10th, was still in the dugout donning his gear. Someone without gear was warming up Willoughby. It was only 2-3 seconds of interstitial airtime, but I quickly realized it was longtime back-up catcher and future Sox announcer Bob Montgomery! Monty had a single, fruitless at-bat in this series, so these warm-up tosses were his most high-profile contribution of the Series.

Here’s what went down in the bottom of that fateful 10th inning: Geronimo led off with a single. Enter Armbrister, whose poor bunt and halting procession to first base resulted in Fisk, a Hall of Fame catcher, throwing the ball into center field. Geronimo to third, Armbrister on first, nobody out.

Johnson naturally argued the non-call long and hard, even demanding that Barnett consult the second-base umpire. When DJ finally departed, the sheer injustice of his team’s predicament sunk in with Fisk, who ripped Barnett a new one all over again. I mean, he was in the umpire’s face for another 45 seconds — he’d surely have been thrown out of any other game. If Pudge had turned to the crowd in Cincinnati and started yelling, Attica! Attica!!, no one would have missed the allusion: “Dog Day Afternoon” was the no. 1 box-office film in the country that October of 1975.

Once again, despite the dire circumstances, Johnson never put a foot wrong. Willoughby exited, making way for Rogelio “Roger” Moret, one of my favorite Sox of the early ‘70s and just the strikeout pitcher required in this situation. Pete Rose was intentionally walked, setting up the lefty Moret against the lefty Griffey. But no! Sparky countered with right-handed Merv Rettenmund, whom Moret promptly retired on strikes. The rail-thin Moret went a remarkable 14-3 out of the bullpen in 1975. Kurt Gowdy, in the booth this night (in place of Garagiola), informed viewers that Moret was 6’4”, 170 pounds, then later described him as “willowy.”

Naturally, it was Joe Morgan who eventually won Game 3 — first with his unassisted DP in the top of the 10th, then with the game-winning RBI half an inning later. With the bases juiced and just 1 out, the Sox infield was back and the outfield in: to haul in a short fly and perhaps cut down a tagging runner at home. Morgan mooted both scenarios with a long drive to center that Fred Lynn tracked for only a few steps before turning away, slumping his shoulders and jogging head-down to dugout, through an infield mass of jubilant Reds.

Lynn was the apple of my eye in 1975. Watching these games after 50 years, countless memories of him, his teammates and this series were dislodged and enjoyed all over again, thanks to the online magic of YouTube. But not this game-ending sequence that long-ago October night. I remember the image of that ball bouncing unmolested and unchased to the wall like it was yesterday. It has never left me.