[Ed. This piece appeared 25 years ago in a magazine called TravelGolf Maine founded by a fellow named Park Morrison. It didn’t last long (1998-2001) and, sadly, Park passed away last year. I’m including the story here because surely it never made it online — and because it appeared, in print, under a favorite pen name of mine. Another serendipitous fact: When I traveled to Lovell, Maine to “research” the story, the course ranger, lounging in a cart parked by the first tee at Lake Kezar CC, was none other than Bill Bissett, retired athletic director at Hudson (Mass.) High, one of the schools covered by The Hudson Daily Sun, where I served sports editor from 1989-90.]

By Henry Choi

Opinions differ when it comes to appraising so-called schizo layouts, those courses where one nine barely resembles the other. In northern New England — where scads of nines were laid out in the 1920s and ‘30s, only to be expanded many decades later by different architects — the issue is more salient than perhaps anywhere in America. Because there are just so many of them, the question remains: Does one decry the stylistic divergence or applaud the diversity?

Two courses in the border regions of Maine and New Hampshire inform the debate. North Conway Country Club and Lake Kezar CC are separated by 20 miles. And yet, the nines on each course feel even further apart, light years in fact, when it comes to style, terrain and vintage. That both tracks remains such good fun tips our fledgling debate toward applause.

This part of New England is remote but hardly underdeveloped. The resort nature of North Conway, N.H., cannot be lost on first-time visitors to its eponymous, semi-private country club, where the 1st tee is set back just 50 yards from a bustling main drag replete with myriad factory outlets, hotels and restaurants. Indeed, the clubhouse at NCCC sits directly beside the Conway Scenic Railway Station, a massive, red-roofed, Victorian-era structure painted a vivid shade of yellow.

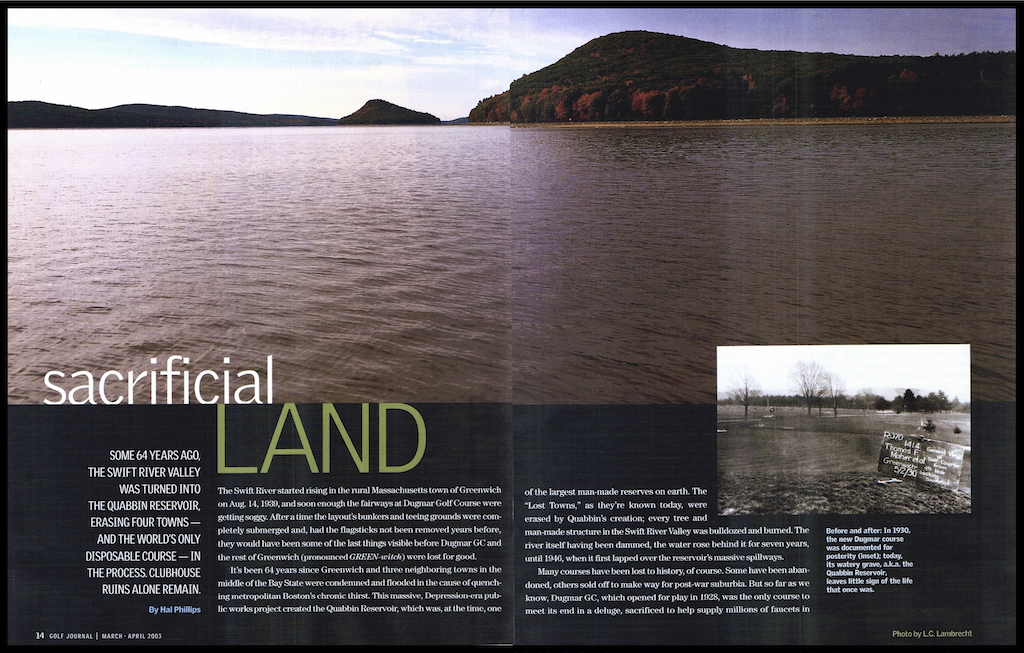

It’s quite a sight, but nothing like the vista next door. The 1st at NCCC (the image above) is one of the great opening holes in all of New England, a 418-yard par-4 with long views of Cathedral Rock in the distance and, of more pressing concern, O.B. all along the left side. It takes some real concentration to block it all out and belt one — right over the train tracks! — to a fairway 70 feet (!) below.

Don’t get the wrong idea, however. The remaining golf at North Conway CC isn’t about dramatic elevation changes. At all. After this inaugural plunge, the course plays entirely in the subtly contoured flood plain of the Saco River. It’s scenic — with the river running through it and White Mountains surrounding it — but it’s relatively flat and eminently walkable.

The opening nine here dates to 1928, when Ralph Barton, a protégé of Seth Raynor, reworked a older, rudimentary loop. The charm of these opening holes lies in the subtleties of their small, steeply pitched greens guarded closely by deep bunkers. The 4th is a wonderful short hole, a make-or-break 140-yard pitch to a putting surface that falls away steeply on all sides. Every so often the land here does move with surprising drama. The 354-yard 5th plays right along the river; the back tee calls for a drive across a bend in the Saco to a swaled landing area, which is then crossed by a stream at 240 yards. The green looks harmless enough, until you look over the back side and see the ground fall away steeply some 20 feet.

The second nine at North Conway arrived much later, in the mid-1960s, courtesy of New Hamster-based architect Phil Wogan, and no — the two loops do not go together stylistically. The front side putting surfaces are set mostly at grade, while the bulk of Wogan’s greens are raised up in mid-century mode made fashionable by Robert Trent Jones, Sr. Yet the backside putting surfaces are quite cool and challenging in their own right, especially the saddle job at the par-3 13th — and the epic volcano that sits at the business end of the sublime-but-potentially-cruel, 434-yard, par-4 14th.

•••