[Ed. This story appeared in March/April 2003 issue Golf Journal magazine.]

The Swift River started rising in the rural Massachusetts town of Greenwich on Aug. 14, 1939, and soon enough the fairways at Dugmar Golf Club had become unseasonably soggy. After a time the layout’s bunkers and teeing grounds were completely submerged, and had the pins not been removed years before, their flags would have been some of the last things visible before this 9-hole track and the rest of Greenwich were lost for good.

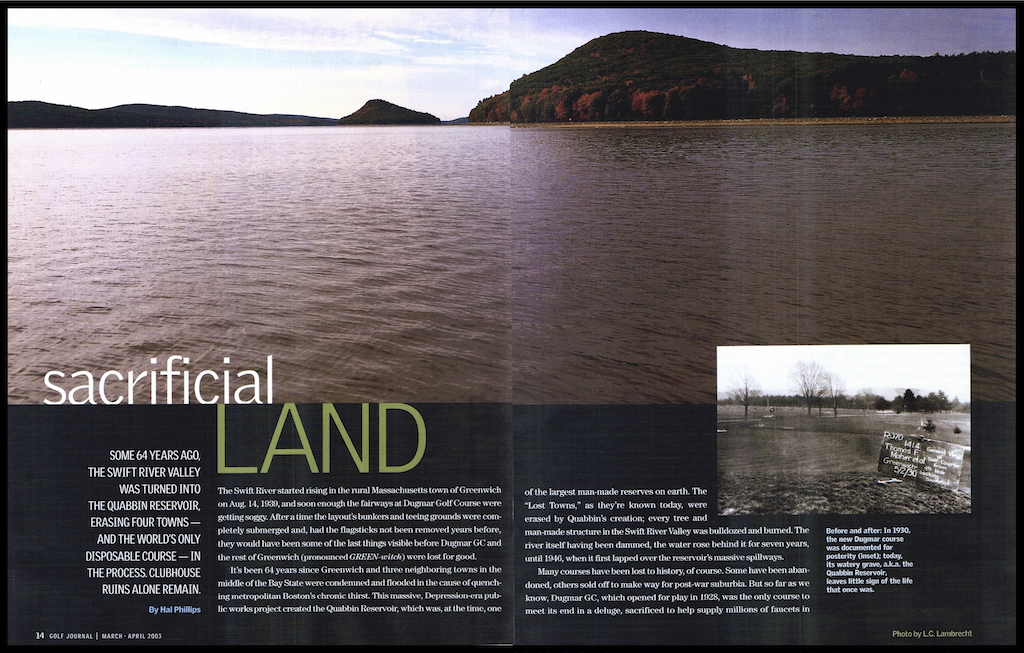

It’s been 68 years since Greenwich and three neighboring bergs were systematically condemned and flooded, all in the name of Metropolitan Boston’s chronic thirst. This massive, Depression-Era public works project on whose ass the loss of Dugmar GC was but a pimple, created the Quabbin Reservoir, then the largest man-made, fresh-water reserve on earth.

The Lost Towns, as they’re known today, were literally erased by the Quabbin’s introduction; every tree, every man-made structure in the Swift River Valley was burned or bulldozed to make way for it. The river itself having been dammed, the water rose behind it for seven long years, until 1946, when it first lapped over the reservoir’s massive spillways.

By then Dugmar GC had been largely forgotten — but not erased, for memories are made of stronger stuff.

Other layouts have been lost to history, of course. Some have simply been abandoned; others were sold off to make way for post-war suburbia. But so far as we know, Dugmar GC — opened for play in 1928, hard by Curtis Hill — was the only golf course to meet its end in a purposeful deluge, sacrificed (along with four 200-year-old communities) to supply tens of millions of faucets in larger communities some 60 miles east.

Hundreds of golf clubs were built, as Dugmar had been, during the heroic age of Jones and Ruth as the moneyed classes sought to bring the same sort of bravado to their own lives (not to mention a place to drink hooch in a country gone dry). More than a few of these establishments “went under” during the ensuing Depression, but none quite like (nor quite so literally as) Dugmar Golf Club, for unlike their unwitting, high-living contemporaries, Dugmar’s developers KNEW the club’s fate before the course was ever built — before the bentgrass was imported from southern Germany, before the elegant stone patio was laid beside the farmhouse-turned-clubhouse, before the first crate of Canadian Club was hidden from view.

It was, in short, a set up: a crafty land deal with golf at its core; a trifle built to amuse its backers, for a time, before enriching them at the public’s expense. “Those guys knew what they were doing; they made out,” recalls a chuckling, 85-year-old Stanley Mega, who caddied at Dugmar GC and still lives close by Quabbin’s shores, in Bondsville. “Those guys knew the reservoir was going in and they made a killing.”

In essence, Dugmar GC was conceived and ultimately proved to be the world’s first and only disposable golf course.

•••