THE HAROLD HERALD BOOK REVIEW

Ambition as a Historical Catalyst:

Burr, Lincoln, 1876, Empire, Hollywood, and Washington D.C.

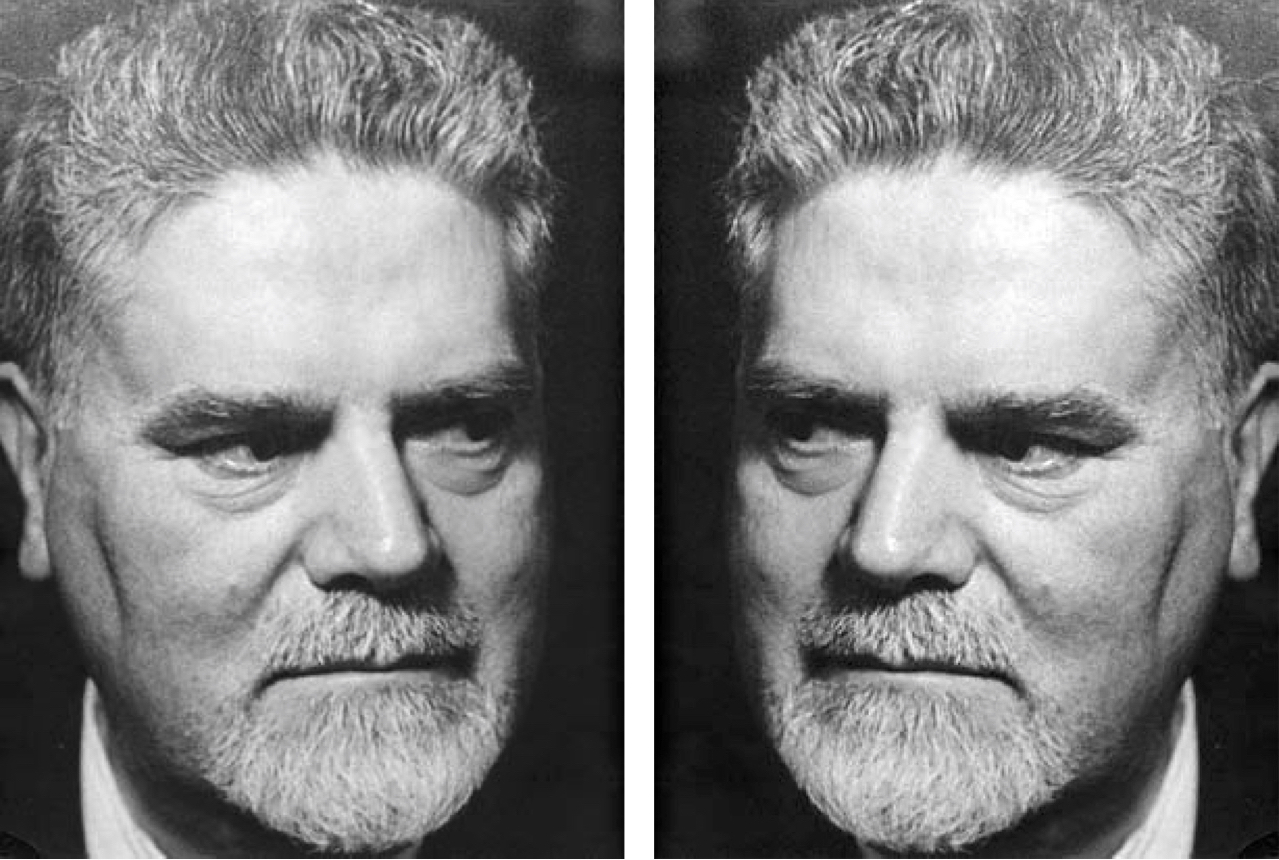

by Gore Vidal.

Ballantine Press, $5.95 ea.

By all rights, Aaron Burr should have been the third president of the United States. If not the third, then certainly the fourth. When he and Thomas Jefferson secured the identical number of electoral votes following the election of 1800, Burr stood aside, accepted the vice presidency, and bided his time. The presidency would certainly be his eventually. Hadn’t John Adams set the executive precedent by accepting the second spot, then ascending in due course? Hadn’t Jefferson promised his support when the time came? But Jefferson would prove unfailingly vague when it came to political commitments. He was wary of Burr and isolated the vice president within his Cabinet. Jefferson wouldn’t allow Burr to resign with honor — until, that is, Burr hadn’t the time to organize a credible campaign for 1804. Jefferson then framed Burr for treason, tried him and while he couldn’t prove the trumped-up charges, the president had by then effectively obliterated Burr’s political viability, thus securing his own and, by naming James Madison vice president, a Virginian ascension.

At least, that’s Burr’s version of events.

Or rather, that’s the version laid out by Gore Vidal’s title character in “Burr,” the first of six historical novels comprising the author’s American Chronicle, which I started in August and have finally finished. By tracking Aaron Burr and his descendants through the nation’s first 150 years, Vidal illustrates how ambition and decidedly unenlightened political scheming shaped and sustained the world’s first modern democracy. At the same time Vidal weaves an enormously intricate, believable tapestry where historic figures full of life mingle with the fascinating Burr and his equally engaging but fictional offspring. Vidal has clearly done a vast amount of homework. Yet while his narrative has an authority born of journals, letters and historical canon, Vidal’s real characters — like Jefferson and William Seward, Lincoln’s ambitious secretary of state — are unfailingly funny, sullen, outrageous, randy, paranoid and sometimes insane. In a word, human. Indeed, they take on the qualities of fictional characters because they’re depicted with such depth, wit and humanity. On scholarly grounds, historians wouldn’t dare recreate dialogue as Vidal has done. Besides, most historians couldn’t do it; they haven’t his skills as a novelist. Vidal can convincingly mimic Henry Adams and Mrs. John Jacob Astor, with equal parts style and integrity, because he’s a novelist with a supreme command of the subject matter.

When Vidal intersperses these historical figures with fictional characters (believably placed in the maelstrom of actual events), it’s hard to remember who’s real and who’s not. The author does his level best to remove any distinction.

Young Charles Schermerhorn Schuyler, a fictional law clerk and budding journalist, tells the story of “Burr”. Schuyler works for the title character and convinces the old man to dictate his fascinating memoir. This Burr does, in part. The bits and pieces of his amazing life — the raid on Quebec with Benedict Arnold, candid Burr-centric portrayals of all the founding fathers, his aborted conquest of Mexico, his many wives, his mysterious relationship with Martin van Buren, rumored to be Burr’s bastard son — are never published as memoir, per se, only as flashbacks set against Burr and Schuyler’s “contemporary” story, set in the 1830s. The young protégé is mesmerized by this window on the nation’s founding moments and men, but he is fairly well knocked to the floor when, upon the old man’s death, Schuyler learns that he, too, is Burr’s illegitimate son.

In “Lincoln,” volume II in the series, Schuyler disappears and Vidal centers the novel around two historical figures: the president and his young secretary, John Hay, who narrates. Schuyler reappears very late in “Lincoln” before resuming his narrative in the third volume, “1876.” Here Schuyler and his daughter hitch their political wagons to the shoo-in presidential candidate, Samuel Tilden, and their social fortunes to New York’s budding Astor-based society. At the beginning of “Empire,” Hay, now President McKinley’s secretary of state, returns as one of Vidal’s central characters, alongside Schuyler’s two grandchildren, Caroline and Blaise Sanford. Secretary Hay becomes Teddy Roosevelt’s vice president upon McKinley’s assassination. Blaise becomes William Randolph Hearst’s dilettante protégé, while sister Caroline — a former schoolmate of Eleanor Roosevelt in England — buys the fictional Washington Tribune, where she out-tabloids both Hearst and her jealous brother. “Hollywood” follows Caroline to California, where she helps pioneer the movie industry (with Hearst). Blaise buys the Tribune and remains in D.C. to savage President Wilson — and back the serenely dim, Republican hopeful, Warren Harding. In the closing novel, “Washington, D.C.,” Blaise is an aging, would-be kingmaker frustrated by FDR’s stranglehold on the body politic. The nation’s capital — a malaria-ravaged swampland in “Burr”; a provincial seat of government in “1876”; now, in 1945, nerve center of the world’s first superpower — has changed, but it still provides a fascinating backdrop for Vidal’s horde of schemers and climbers; all the folks who have made this country what it is today.

Imbued, as I am, with the arrogant notion that scholarly history is interesting enough (blame the Wesleyan history department), I’ve never been a fan of historical novels. Though I’ve always liked Mary Renault (“The Persian Boy”, “Mask of Apollo”), the genre allows too many liberties. Basically, it’s cheating.

But Vidal changed my mind. Well, he didn’t change it… Vidal proves it can be done well, even raised to high art. But good luck finding another author so capable.

Ed. So, I found this piece in an online issue of the Harold Herald, the proto-blog I published via Pagemaker, a Xerox MFM and the U.S. Postal Service in 1994. Disappointed I can’t find the ancient “print” version, as I recall spending a lot of time laying it out to make it look exactly like a NYTimes Book Review page. In any case, it remains an odd mix of fascination and dread to read oneself from 20 years ago, especially as I happen to be rereading “1876” right now. I back most everything I wrote here, save the last bit. I have, in the ensuing decades, found several historical novelists the equal of Vidal, but only in certain respects. Bernard Cornwell — he of the Sharpe’s Rifles series, set in Napoleonic times; an Arthurian trilogy of the highest quality; and several more multiple-volume depictions (of England in the of time Alfred, France in the middle ages, and even America during the Civil War) — is a thoroughly trustworthy historian and expert yarn-spinner. But he cannot write like Vidal. Few can. Renault is fabulous, but Vidal’s “Julian”, which I read after tapping out the above review, beats Mary in her own classical backyard. Hilary Mantel’s 21st Century series starring Thomas Cromwell and Henry VIII (“Wolf Hall” and “Bring up the Bodies” are to be capped by a soon-to-be-released third book) is superb — but she needs a few more under her belt, ideally something from a completely different era, to hang with Vidal.

The best moments in any good historical novel are when the author introduces and puts to lengthy narrative use juicy historical characters — their rendering and their interaction with fictional characters, when done well, can be thrilling. This might happen a half dozen times in any Cornwell novel. In “1876”, it happens every 15 pages: Grant, Mark Twain, Maine’s own James Blaine, James Garfield, an array of New York newspaper editors and publishers, The Astors, Samuel Tilden, even Chester A. Arthur for chrissakes. The density of these non-fictional characters in the narrative is dizzying, and Vidal delights in painting familiar icons in ways that deconstruct our preconceptions while remaining entirely plausible, not to mention historically accurate. This is some of what makes Mantel such a formidable player in the genre: She similarly packs her novels with historical figures, fascinatingly rendered, something her relatively modern subject matter (and our familiarity with many of her non-fiction characters) allows.

The piece de resistance of any historical novel, I’ve learned, is the author’s note at book’s close. Not all of these are handled the same way, but here, typically, the author details the liberties he/she may or may not have taken with historical events and personages. Invariably, they are minimal; it’s in the author’s interest to give that impression, of course. Oftentimes they’ll get into their sourcing, their bibliography, for the same reasons. Either way, it’s clear that extraordinary grounding in a subject is required, alongside and integrated with their abilities as storytellers. I remember when I first read the author’s note for Burr: Vidal basically says, “Everything depicted here is historically accurate; everything the non-fictional characters are quoted to have said was taken directly from primary sources, i.e. their letters, correspondence and memoirs.” I just skipped ahead last night to the Author’s Note for “1876”. It’s similarly brief. Vidal was obliged to move up Twain’s publication of “Huckleberry Finn” so it might be discussed during the author’s dinner at Delmonico’s with Schuyler in June 1876. Similarly, the massacre at Little Bighorn happened in July, but word of it didn’t reach back East for several weeks. Vidal wanted it in the air at the Republican convention in July, so he took that liberty. But that’s it. Everything else fits together like a sprawling Roman floor mosaic, the sweep of history accented here and there by bits of fictional color.

What I didn’t know in 1994 was that Vidal wrote these books out of order, as it were. “Washington D.C” came first (published in 1967), followed by “Burr”, “1876”, “Lincoln”, “Empire” and “Hollywood”. What I couldn’t have known back then was that he would add a seventh volume, “The Golden Age”, that chronicles America during the Cold War. In this coda, Vidal takes us right up to the year 2000 (the year it was published), by which time the original thesis laid out in the very first book and supported throughout the series — that America’s republic, always built on the not particularly reliable or durable foundations of corruption, ambition and privilege, had, with the close of WWII, finally given way to outright empire — had indeed come to pass. “The Golden Age” features the broad cast of historical characters any reader of the Chronicle might expect, plus one that comes as a mind-bending but pleasant surprise: Gore Vidal himself.

Vidal never cottoned to calling this series his American Chronicle. That came from the publisher apparently. He preferred Narratives of Empire, and one can see why.